JS Orellana and Corleto had been threatened by the government at the time, and the work was canceled.

JO Yes, it was banned by the army at the time of the Serrano Elías government.

JS Elías banned En los cerros de Ilóm because it addressed the issue of Guatemala’s internal conflict. Orellana used art to denounce it. I should say that Orellana’s work has always been a denunciation. Ever since he started talking about Humanofonía in 1971, the music of hunger. That’s where that approach came from, and it went on, and the denunciations got stronger in En los cerros de Ilóm. The play couldn’t go abroad, and that created a great frustration in people—in everyone, the cast, the production. We weren’t able to show the play but that didn’t mean we stopped working with Orellana personally. My group got really into Orellana’s music, we clicked.

AT What’s your group?

JS Coro Victoria. The Coro Victoria is an artistic musical institution dedicated to presenting art for art’s sake, with a very unique aesthetic approach. Coro Victoria complements the music with acting, with drama, so that the message is more effective. It’s not the same to sing a work of Orellana’s musically as it is to act it. The choir’s message is not solely musical; it’s also a message about acting, about drama, which allows the composer’s message to be clearly conveyed. From the audience’s perspective, it doesn’t matter that they don’t speak the language. Orellana doesn’t use any concrete language; what he uses are phonemes. They’re Indigenous phonemes from Guatemala that allow for a clear message. The Coro Victoria has been like the base that has allowed for many of Maestro Orellana’s works to be shown.

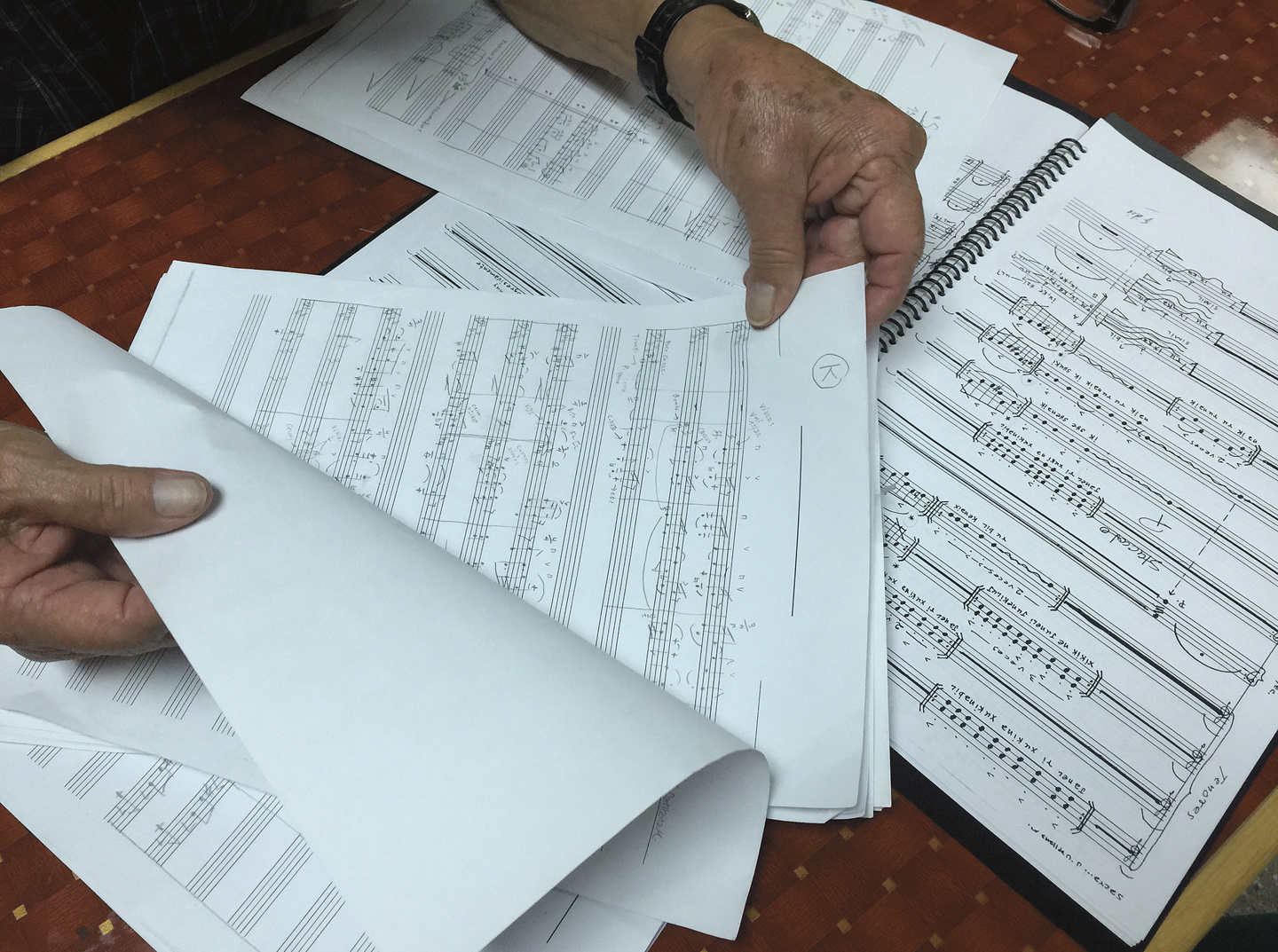

The Maestro and I have forged a deep relationship over the years. I have an intimate perspective on his artistic, aesthetic, and creative point of view, and I’ve gotten to know a bit of the Maestro’s human side, which is also very important. In 1999, we presented a project at the Fifth World Symposium on Choral Music in Rotterdam. That provided me with a great deal of new knowledge. It turned out that the Europeans worked with a different choral structure than the one we used in Guatemala, and so the Coro Victoria came back and worked with that structure here—I suggested it and the choir accepted. Orellana became the group’s composer. I also had my vocal coach, my professional choreographer, who had graduated from dance school … so I had all the structure Europeans work with. It’s a great blessing to have a living composer who’s willing to visit the group and teach us how to approach the music. We still have everything we need. We’ve toured Asia, America, and Europe. So all that has led us to strengthen our ties with the Maestro.

AT How would you describe the evolution of your approach to music over the past six decades?

JO It all started with the Humanofonía of 1971. That emerged from my growing awareness of sociopolitical circumstances, of a society suffering from labor exploitation, the repression of unions, things that exacerbate conditions of poverty and hardship. When I returned to Guatemala from Buenos Aires in 1968, where I had soaked up what was then the European avant-garde, I was going through a crisis. On the one hand, I could have kept on being an avant-garde artist in the European way, and on the other hand, I could have kept on making outdated creations of nationalistic music.

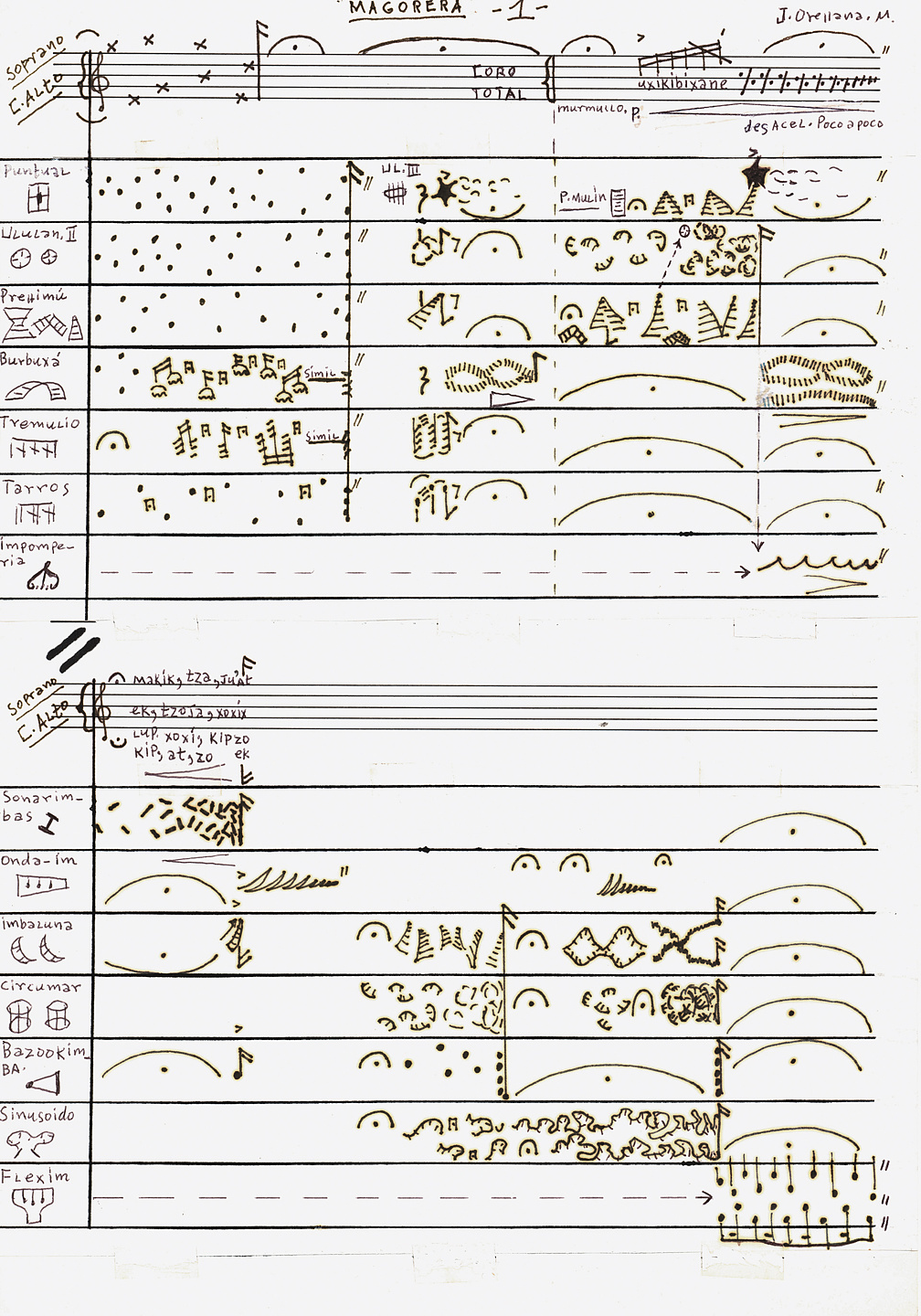

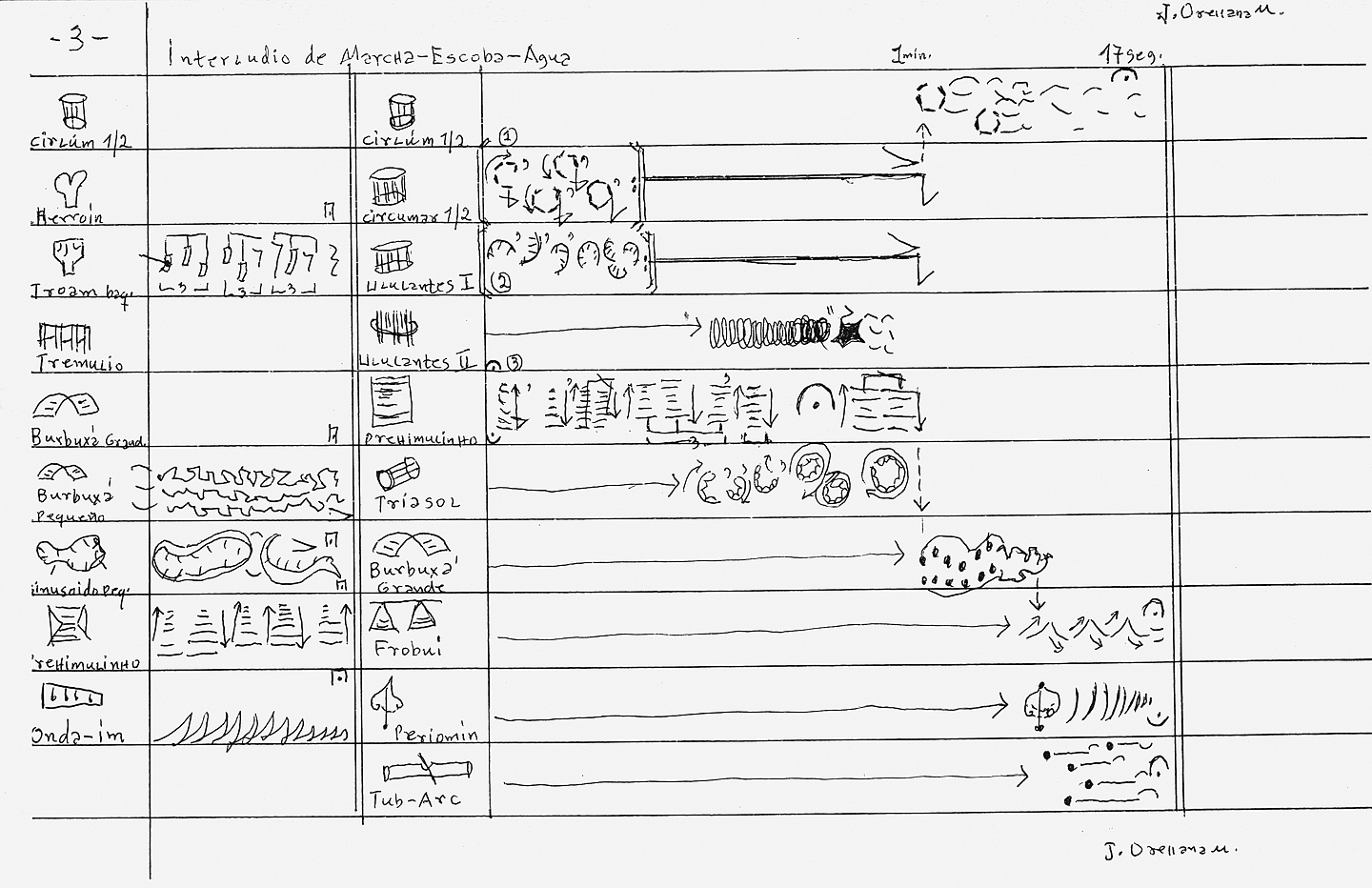

That crisis fortunately led to the Humanofonías—I was driven not by fixed or metaphysical objectives but by an intuitive flow. I began to realize that singing was implicit in the accents of spoken language, and that in order to capture a sound landscape of our own—since one of the values of Latin America was the Indigenous languages, fragmented and joined within the same tenor of expression—I created a series of layers. All this I called “humanophonal.” I then took on the task of recording different environments in which I was able to create certain contrasts. For example, I’d record the movement from inside to outside a church. I’d arrive out at the atrium where the voices of the beggars could be heard, either in Spanish or in an Indigenous language. There I found a contrast between the cold litanies and the lamentations of the beggars. So when I recorded sounds of a rally, for example, with the sounds of the marimba and then the Sonarimba [the first of the sound utensils designed and built by Orellana], I was acting within my own context of Guatemala and Latin America, and simultaneously with the avant-garde of the time—I was creating musique concrète.

With Humanofonía, my intuitions and the structures of my sensibility became all the more acute. There’s an increase of feelings and ideas, and that’s how they evolve and continue to evolve; for example, Malebolge [referring to the eighth circle of hell in Dante Alighieri’s Inferno, the first part of the Divine Comedy] based on sounds of expiation in prisons, sounds of torture, sounds of drowning. Malebolge begins a body of work within the frame of rebellion, each time more vehemently, each time with greater desire for depth, to the point where, for instance, I arrive at the exaltation of the marimba in Evocación profunda y traslaciones de una marimba. A kind of synthesis is projected in Ramajes de una marimba imaginaria, while in Marimba en el destierro [Marimba in exile] it already exists, linked to that movement from internal to external events. As a way to directly represent rebellion, the other part to Ramajes de una marimba imaginaria is called “Marimbalzada” [Rebellious-Marimba]. From that comes Sacratávica, Imposible a la X, and En los cerros de Ilóm, emblematic works which form part of my legacy, which could be considered a compendium or zoom toward the Sinfonía desde el Tercer Mundo. You could say that since the Humanofonías of 1971, I was already constructing the symphony that will be presented for documenta 14.

With Humanofonía, I began to express social consciousness well beyond the norm. Much of my work evolved along those lines. Apart from that, there are works that are still unknown, songs that I only started writing. One of those is called “Pepita y el Río,” dedicated to the memory of María Josefa García Granados. I wrote songs dedicated, for example, to a woman from Zacapa, but those were more for amusement. I’ve also created a kind of song that is more like a choral poem, which is called Elegía a una migrante muerta en camino [Ballad of the migrant who died on the road]. I based that composition on the true story of a Guatemalan woman who died of thirst going after the American dream. Maybe this constitutes a small change in direction, although still it is set within the greater structures of my sensibility, of sono-social circumstances or, more realistically, of sociopolitical circumstances.

SB Can you tell us a bit more about when you went into the conservatory, when you started formally studying music and experimenting with electroacoustic music? How did that lead you to the fellowship in Buenos Aires, which marked a “before” and an “after” in your life?

JO I was a violin student and a traditional harmonics student, and then I studied composition. When I started at the conservatory, everything I composed was very chromatic; I was always trying to move away from tonal centers. Soon I realized that what I was searching for had already been discovered by Arnold Schönberg. It was dodecaphony, which he had already created in 1921. I had those intuitions from 1963 to 1965, but feeling like I had reinvented the wheel helped me to find what I was searching for. This created a balance, a break from the disequilibrium a person might face when working within one system and then abruptly changing to a different system. So I created the Ballet contrastes, having already learned a lot about counterpoint, orchestration, compositional structure, and intuitions. I sent this work to Buenos Aires and that’s what got me the fellowship at the Instituto Torcuato Di Tella.

SB What was the atmosphere like at the Instituto Torcuato Di Tella, and how did this experience affect your world consciousness? Were there any people or ideas you came into contact with which continue to inspire your work?

JO Yes, I had a great professor at the Instituto, his name is—he’s still alive—Francisco Kröpfl. He was one of the few professors I’ve met who was obsessed with his students understanding everything clearly. He’d sometimes even meet on Sunday afternoons, giving up his Sunday off to meet with students to see if they had any questions or doubts. Then there were also the classes taught by Alberto Ginastera and visiting professors from Europe. One of the teachers who had a strong influence—not so much in his technique but in his vision for contemporary music at that time, it was 1967—was composer Luigi Nono. Pierre Boulez, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and Nono were the three main figures in the avant-garde who were revolutionizing sound art. And they all came from the dodecaphonist approach of Schönberg. All of this gave me a very general vision of what had happened and was happening with music in Europe and in other parts of the world. I became aware of the differences between the musical development of Latin America, and more than anything Central America, and what was happening in Europe. This was what prompted, as I said before, the crisis that I resolved with the Humanofonía.

SB What was it like to come from Guatemala, where there were so many limitations on what you could do, and arrive at such a well-funded institution in Buenos Aires?

JO They had an audiovisual experimentation room, an auditorium. They gave all the young people involved in theater—all the young playwrights, with their different approaches—the chance to experiment there. And I remember Jorge Romero Brest, a very eminent Argentinean, who was the director of the audiovisual experimentation room. Within that complex there was the Latin American Center for Advanced Musical Studies. Each of the fellows had a rehearsal space with their own piano, a small music library, a small reference library. We had a scholarship of 70,000 Argentinean pesos, which allowed us to get on freely in every aspect of life.

When I arrived I realized that for the artist—not only the composer, but the painter, the sculptor, the new writer, the young writer—there were a lot of stimuli and a lot of support, which was incredible to me because in my country there’s a great lack of not only financial or academic support but a great indifference and a lack of appreciation. At home, almost everything emphasized the traditional, and there were particular groups who had direct relationships with the people in charge, who were rarely the ideal people. When the fellowship ended, I hated not being able to stay for longer.

SB I understand that you created the sound utensils after coming back from Argentina and finding that the technology for the electroacoustic experimentation you relied on there was not available here. Is there a kind of hunger that generates beautiful innovation, or is it more a sense of self-determination?

JO Well, I was able to resolve that crisis with the Humanofonía. I realized I didn’t have the technological resources I’d had over there. When I was there I made Meteora, which was between electroacoustic and electronic music. I was forced to use artisanal resources when I created Humanofonía. From a technical point of view, it was a work with a certain technical poverty, but with an aesthetic, sociological, and ideological objective well beyond what those technical resources could allow.

To answer the question, I believe the sound utensils were a form of self-determination, though chance played a role. For instance, in the 1971 Humanofonía, when I realized that the marimba was a constant in our sound landscape, an idealization of the marimba began. It was then that the sound utensils began to take shape. So there were certain cyclical automatisms involved. [Visual artist] Carlos Amorales gave a very good explanation. When he noticed that the bars of the marimba sounded as percussion does, bouncing off each other in a cyclical manner, he thought that was like doing away with electronic music sequencers, that they had been substituted with an artisanal method.

SB It was a very clever solution because you managed to fill the void caused by not having the technology but also, by taking on the marimba, it became a way of reaching an audience here; given that when you returned to Guatemala there wasn’t necessarily an audience for the kind of work you were developing, because there wasn’t that kind of education. It was like killing two birds with one stone.

JO Exactly, exactly. Except I haven’t been able to link the two conceptually in the way that Carlos did, in the way he fused the two things.

AT I could be misreading this, but in Ramajes de una marimba imaginaria the marimba is given a narrative character, a personality, a life. Would you say the same of your sound utensils?

JO Yes, the marimba has a life of its own—the image which exists in the collective memory, the image of a national instrument which embodies the feelings of a people, the loves, the nostalgias, the sadnesses. So the marimba has that life, it presents that life in Ramajes, and the sound utensils, along with the narrator, establish those national dialectics—they could be considered the fantastical marimba. When drawing from regional pieces to reflect the marimba’s traditional character that’s what grants the marimba a special life—or at least here, because of how Guatemalans have appropriated it. These works are really the personality and life of the marimba, but when those regional pieces are played in a different context, one that is also within the same world as the marimba, that’s when the marimba and the sound utensils each take up a life of their own.

SB That connects very well to the use of characters in your different compositions. They wind up going beyond musical experimentation. There’s also a narrative story that ties to your interest in literature and allows you to achieve what you’re trying to carry out musically.