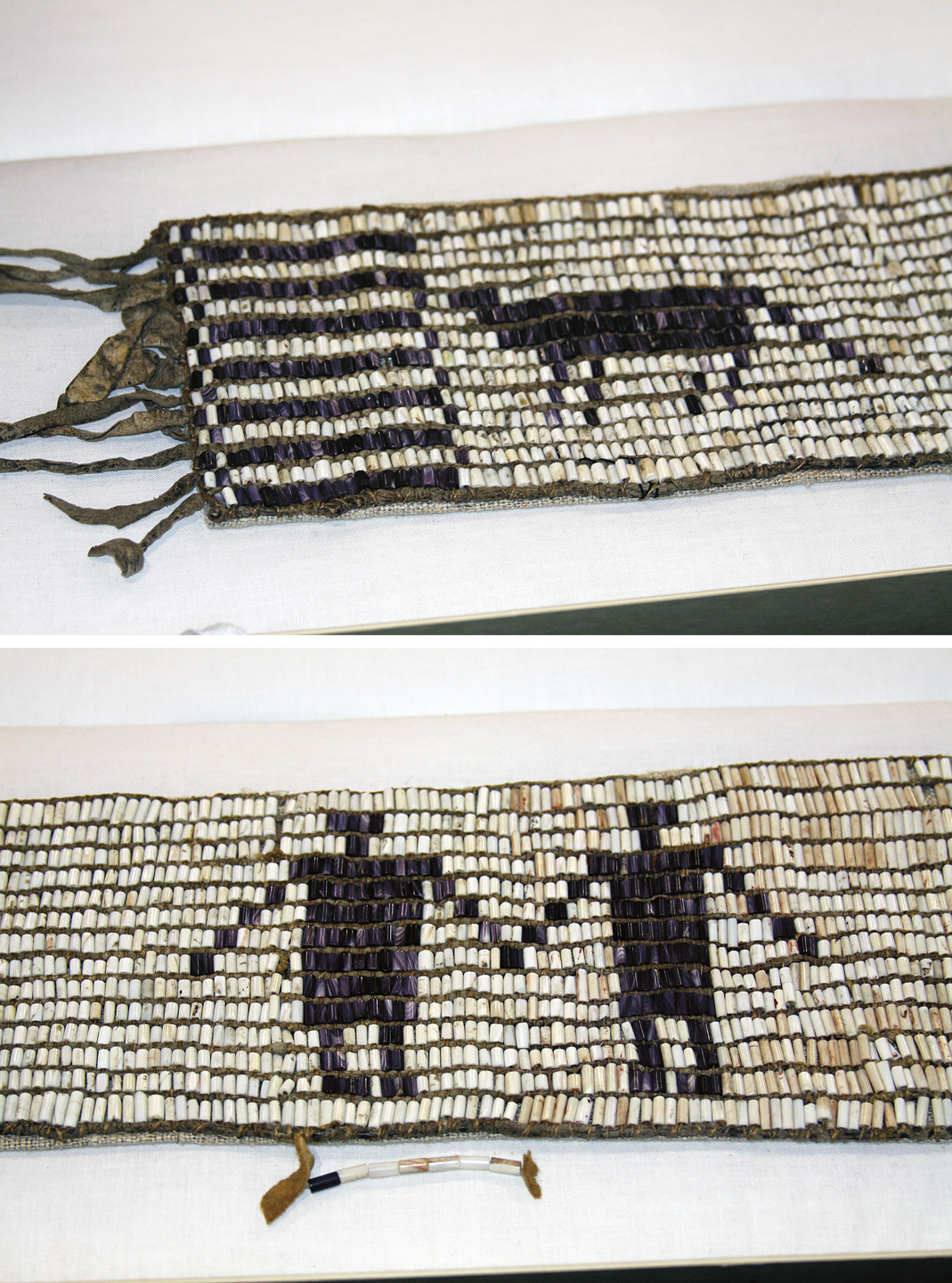

JR I think what you and I, Maria Thereza, are both talking about is that in order to learn these ideas, it has to be bodily; it has to be experienced. This is where oral recitation is so important. We talk about talking to wampum. People more knowledgeable than me may understand it on a different level, but it’s really just making these ideas present. When you talked about the children bringing these words to life that is like the function that wampum takes in our community. It brings these ideas to life.

It is about that relationship to material that seems to be really important, as far as wampum is concerned. When they do the recitation they physically hold the wampum up. All I can say, having witnessed it, is that it is just incredibly powerful. It is like something very old is happening, yet at the same time, it’s like, here it is: renewal.

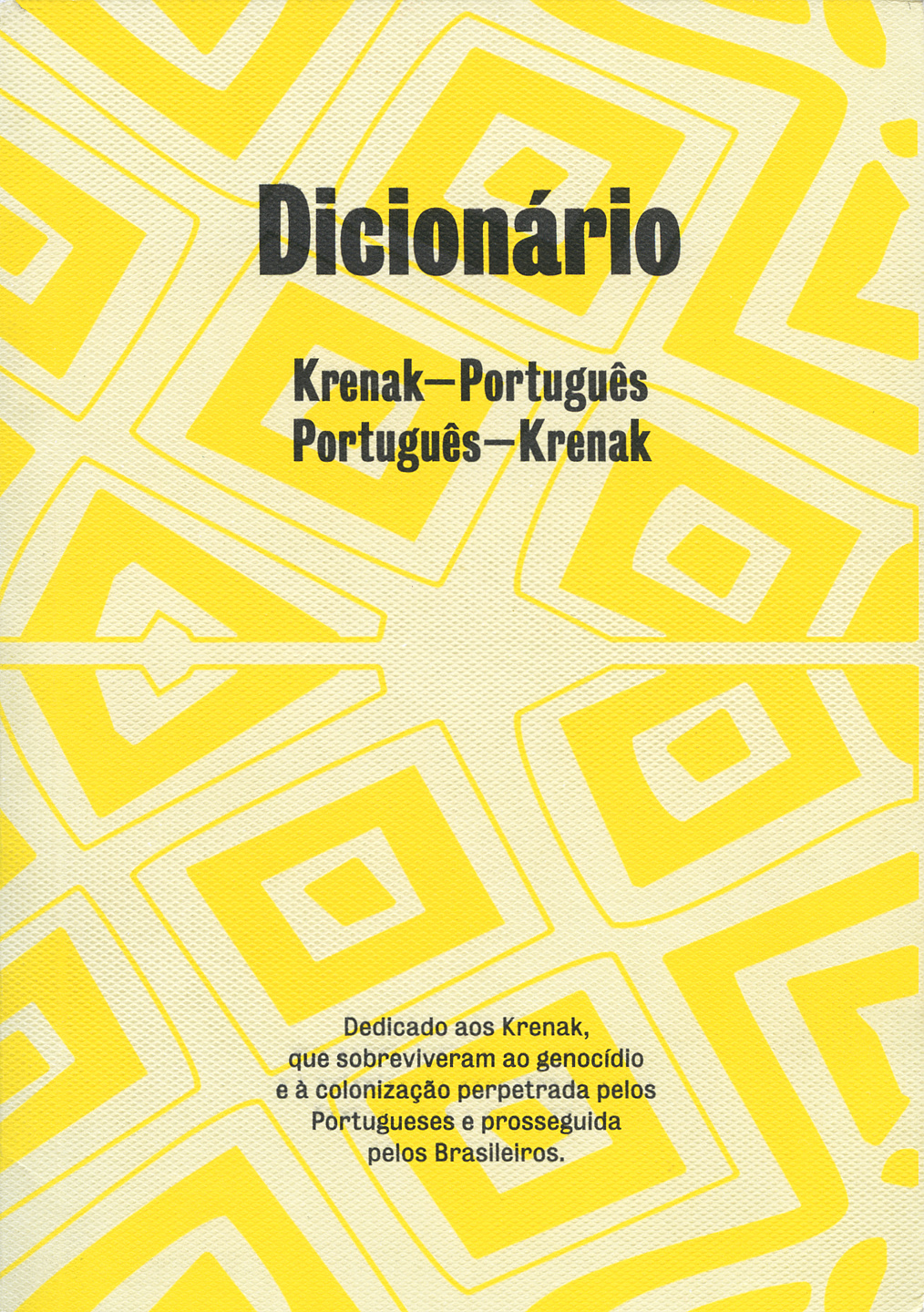

CH The dictionary provided a way to bring about the renewal of the Krenak language. But its distribution became a complex question—it also became an opportunity for members of the Krenak community to assert control over knowledge and its circulation.

MTA After the Bienal, we had to decide what to do about that. Brazilians had been coming up and asking for copies of it. I said, “Well, they are not mine to give. Give me your e-mail, and I’ll get back to you.” So then Shirley and I talked to figure out what the policy would be. She was very clear. “For five hundred years they never wanted to talk to us, only kill us,” she said. “The dictionary is in German, not Portuguese—Brazilians were never interested in us. Therefore they don’t get access to the translation.” It was a wonderful idea that clearly illustrates the survival tactics of the Krenak people.

Shirley did say that Germans could have access, though. But then a German student wrote to me, asking for a copy in Portuguese, because he was doing a thesis on the Krenak language at a Brazilian university. I wrote to Shirley; I said, “What do we do?” She said if it was a German doing a thesis in Germany we could give it to him. But since he was working with the Brazilians, no. I really admired that ability to look at the situation very clearly in each case and deal with all the political subtleties. When the dictionary is exhibited outside of Brazil, it is in a simple Plexiglas box. When it is exhibited in Brazil, the box has a lock on it.

JR At the recitation of the Kayanerenhtserakó:wa, you are not allowed to record or write anything down; only the chief’s council has the authority to document the recitation. And if you are not part of the Haudenosaunee communities, unless you were invited you would be asked to leave. It’s not a performance for the edification of those who are simply intellectually curious. This is a part of our strategy for continuing our way of thinking.

Our colleague Audra Simpson, a Mohawk, has a theory of refusal as it relates to access to our traditions, which she presents in her book Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States (2014). She articulates it through the way in which identity is constructed in our communities.

CH Refusal is a subject that comes up in the conference scene in Iracema (de Questembert)—is that right, Maria Thereza?

MTA In that part of the film, Iracema attends an international conference and challenges France about its colonies. Iracema is an Indigenous woman who inherited an estate from a man who thought he was her father, and she was subjected to much resistance from the racist French. So it was important that she denounce the continued colonization by France of Réunion, Tahiti, other parts of the South Pacific, Guadeloupe, and French Guiana. We had some young students from different art academies come in and play the audience. Shirley—who is, again, playing Iracema—has never been invited to participate in any conference with Brazilians in Brazil. She hasn’t been invited to give a talk on the land struggle, on their cultural policies, anything. She said, “Thank you, Maria Thereza, because at least once in my life, even though it was only fiction, I was part of a conference.”

That is the level of Brazil, the stupidity of reality. At most, if they’re forced to, a Brazilian institution will invite a Native person to speak and pair them off with an anthropologist as a partner. At the 2006 Bienal de São Paulo—the theme of which was “How to Live Together”—we publicly questioned the lack of Indigenous land rights and also of indigenous representation, and they responded by inviting Jimmie Durham to come and speak … with an anthropologist! Of course Durham refused the invitation.

CH Jolene, your work has also demonstrated how we as Indigenous peoples have always been in a dialogue with Europe, whether this is relative to trade or the creation of treaties and other international agreements, most recently the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples adopted in 2007. I think sometimes that people want to think of us as separate—or irrelevant to conversations on the nation-state, as the comment by Shirley Krenak implies—even within the context of our own home countries, when the reality is anything but. I think it’s important to assert international relationships, particularly now with the ratification of the UN declaration by many nations including Canada, the United States, and Brazil, and the hope that it will provide the framework for further agency for Indigenous peoples in all parts of the world.

JR Yes, this idea that Europeans came here and controlled the dialogue, or controlled us, I think is a turn of events based on genocidal acts of war. For three hundred years, Haudenosaunee people tried to maintain a diplomatic relationship with the French and the British, and then the emergent American government made diplomacy no longer tenable. Wampum really embodies that negotiation, the way in which we consolidated these ideas.

The objects, Candice, these material things, that is what the knowledge holders say: “They will present themselves again.” It is framed in this language of repatriation. Our people discuss how the ceremonial objects are returning to our communities after being hidden, either by museums or ignorance.

CH Museums are described by the scholar Ira Jacknis as reflexive institutions that present one’s culture back to oneself. Maria Thereza, I thought you used that principle to great advantage in the context of Fair Trade Head when it was displayed as part of The Museum of European Normality, a project you created in collaboration with Jimmie Durham (which included the participation of Michael Taussig) for Manifesta 7 in 2008. In the museum, “Europeanness” was reflected back onto itself through the display of artifacts, anthropological studies, and philosophical texts on what European normality looks like post-1945 via a study of its habits and public rituals. I thought the project was very successful in how it exposed contradictions within the self-narration of the West.

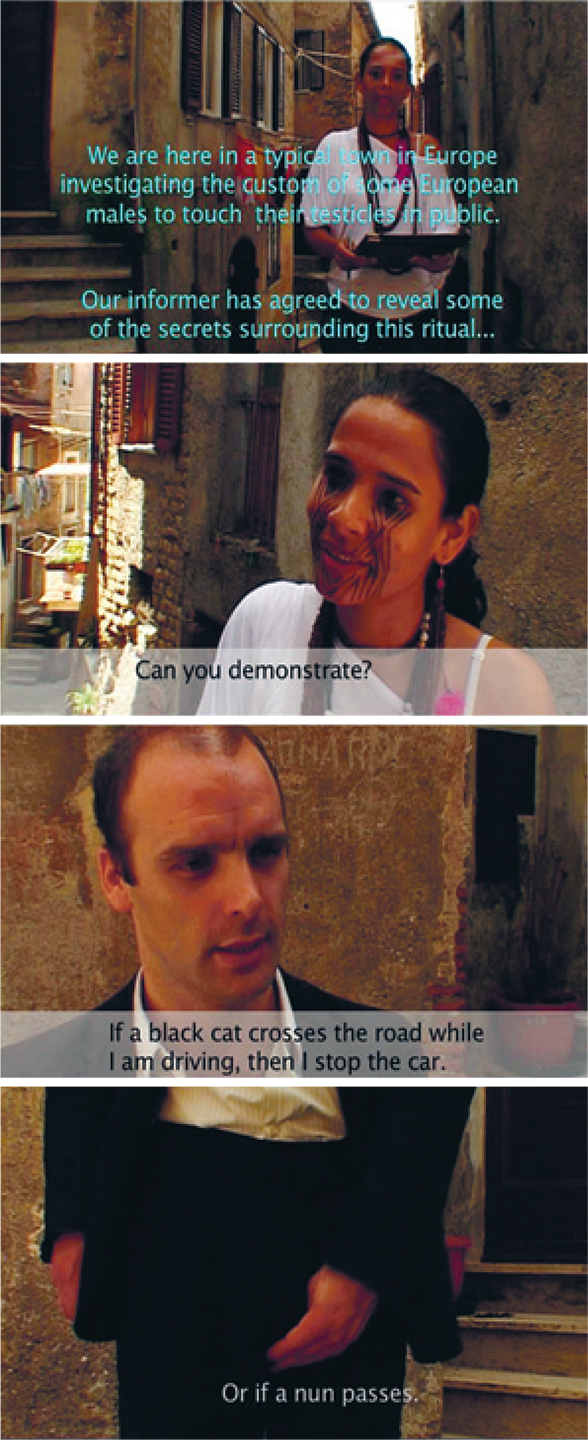

MTA Actually you can see it even more clearly in the video Tchám Krai Kytõm Pandã Grét (Male Display Among European Population) (2008). I was living in Italy, and I noticed that the men are always touching their crotches. I realized that, when I see this in Brazil, it isn’t a local thing; it was imported from Europe.

I decided I would just write to all my male European friends and ask, “When do you touch your crotch and why?” The Northern Europeans, in Sweden and Norway, they say that they never do such a thing. Then you get to Portugal, Spain, and Italy, and there is a whole list of reasons. If a Catholic nun passes you, because she is celibate and you do not want to be, you touch your crotch. If a black cat crosses your path; if a friend says he was just fired from his job; if the mirror breaks, etc. There were more than forty responses I could have used if I had doubled the length of the film.

I screened Male Display in Finland, and an Italian curator was very offended by it. I said, “Well, this is a video about a European ritual. We are looking at it as something very strange that is not part of our cultural stuff. Just like you look at our stuff, and we are looking at your stuff.” The curator said, “But that is not a ritual.” She couldn’t stand the fact that the word ritual would be connected to a European population. I told her, “The definition of ritual is to perform an action over and over again. You see this all the time in the streets of Italy, in the streets of Portugal, and the streets of Spain—every day, every morning. What else can you call it?”

This is what is nice about doing the project, this reversal. All of a sudden they have to do a double take. They expect to be in the position of the ones who study, but they are forced to realize that there are other people studying them as well. In Europe, European culture isn’t in the museum of ethnography. When I go to one, I always do this little performance for myself; I ask, “Where is the Italian section?” or “Where is the Milanese section?” They say, “Oh, that’s not here in this museum—that would be in the fine arts.” That in itself reveals everything they think about ethnography.

CH Often, objects of ethnography are considered outside time: once contained within a museum or placed on public display, their usual life cycle is denied—totem poles, for example, are meant to fall and eventually decompose on the ground; for some it is when a memorial pole falls that the spirit of the person it was carved for is released. In a museum, it is as though they are petrified or reified. Was this something you both have considered in your work—how, in a museum, these objects are not only taken out of their life cycle but are also never allowed to rest, because they are permanently on view? How then do we again give agency back to not only the people whose lives are intertwined with the objects but to the objects themselves.

JR When wampum belts are made public at the Kayanerenhtserakó:wa, the knowledge contained within them is activated. Something similar occurs when the belts are used in key treaty enactments, for example the Border Crossing Celebration that commemorates the Jay Treaty of 1794 (which began through the efforts of the Indian Defense League of America, founded by my grandfather, Chief Clinton Rickard, in 1926). Haudenosaunee people march in our homelands at the border between the United States and Canada to claim our right to unhindered passage in our ancestral lands. To take another case, every year on November 11, G. Peter Jemison, a Seneca artist and Faithkeeper, leads the Canandaigua Treaty of 1794 enactment, which marks the day and location that the United States, by its own law, recognized Haudenosaunee sovereignty. The belt confirming this relationship is called the George Washington Belt and is a covenant belt that depicts the thirteen original United States. At the Canandaigua Treaty march, the George Washington Belt, the Hiawatha Belt, and the Two Row Belt are carried by chiefs who hold the same titles as the men who signed this treaty with the U.S. in 1794. Because the belts are a living record of this relationship, the chiefs are not performing the past but enacting our present.

I don’t think that most people understand the significance of this kind of action. It has taken me a while to really understand how profound it is, and the depth of the role that wampum play in our lives. So it’s not simply about recovering something from a museum.

CH Of course, in order to even begin a conversation about a community’s rights to their objects and knowledge, its members have to possess very basic human rights. What about the rights of the people themselves? How has the status of Indigenous people in Brazil changed since the reformist constitution of 1988?

MTA A good example is something that just happened, in December 2015. There was a proposal for a law that had passed through the legislature. It was a very simple thing: it would increase the teaching of Indigenous languages, extending it from grammar schools to high schools and universities. One concrete example of how this would affect the Indigenous population was that of a Tucano doctoral candidate at the University of the Amazon who wanted to present his thesis in his own language because concepts in it are not translatable into Portuguese.