Silence 1

The sense we have is that in the vast expanses of space between celestial bodies there is a void. Hence, total silence. The Greek word for space is διάστημα, which means literally in-between. It is not surprising that the word was used initially to determine the space between sounds, since the understanding of sound (and, of course, music) was essential to the ancient Greek contemplation of the universe. What Pierre Schaeffer, the founder of musique concrète, would come to call “the acousmatic experience,” the ancient Greeks considered to be fundamental to physics. One listens to the universe, before anything else.

Perhaps a century from now, if humanity continues to exist on the planet, September 14, 2015, will mark the date of another sort of Copernican revolution. On that day LIGO, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, recorded the sound of two black holes colliding about 1.2 billion years ago. LIGO is a giant listening machine focused on the outer edges of the universe: a pair of L-shaped observatories located 1,900 miles apart (in Hanford, Washington, and Livingston, Louisiana, in the United States), where ultra-pure mirrors at the end of each arm, isolated from vibrations, were set up to detect passing gravitational waves. Except that gravitational waves, until this moment, existed only in theory—Einstein’s general theory of relativity that predicted, mathematically, the folding of space as a result of massive gravitational ebbs and flows. The LIGO machine registered the universe’s confirmation of a human being’s theory, which is based—like all theoretical physics—on the assumption that the universe works according to an unwavering mathematics, even if provisionally such mathematics are unobservable or untestable in any physical sense.

The numbers on this occasion are stunning all around, at both macro and micro levels. The energy released from the collision 1.2 billion years ago of two black holes (the size of thirty-six and twenty-nine suns each (combined to sixty-five suns), now thought to have been twins from the core of an unfathomably gigantic star) is calculated to be fifty times greater than the output of all the stars of the universe combined. This inconceivable space storm that produced a glitch in the folds of space moved the LIGO mirrors by a mere 4/1,000 of the diameter of a proton, which is itself 10(–15) meters. The gravitational space fold produced a swishing sound moving across the range of low to middle C that lasts barely three seconds.

No matter the significance that the last part of Einstein’s theoretical prediction was confirmed, the most important thing in this whole affair is this chirp. If Galileo inaugurated modern astronomy’s reliance on telescopic vision now expanded across the electromagnetic spectrum, the LIGO event has changed the paradigm. As Szabolcs Marka, a Columbia University physicist who is a member of the LIGO project, put it: “Everything else in astronomy is the eye. Finally, astronomy grew ears. We never had ears before.” An extraordinary realization, given that from the days of Thales and Anaximander of Miletus in the sixth century BCE the physics of the universe exceeded the visual domain. Before being the object of abstract mathematical thought, the universe is foremost an acousmatic experience. Silence is its in-between. It begs us to listen.

Masks 1

The horseshoe crab is not a crustacean. It is a marine arthropod that is closer to the arachnid family. These odd creatures live in shallow ocean waters off the eastern coast of North America and the East and South Asian seas. Because the species is 450 million years old they are considered to be living fossils. In other words, they carry with them the living history of planetary being. Horseshoe crabs have nine different eyes spread throughout their body; their visionary spectrum includes the ultraviolet range. They are veritable blue bloods because oxygen is not carried in hemoglobin but in hemocyanin, a copper-based metalloprotein. Because of anti-pathogen bacteria properties in their blue blood, horseshoe crabs are blood harvested (this is the phrase)—partially bled and released back into the ocean. Mortality from blood harvesting for the purposes of medical science is low but not nonexistent, while some prohibitions against hunting horseshoe crabs for fishing bait have now been instituted because horseshoe crab depletion affects severely the environmental stability of migratory birds. The human animal is distinguished by its intervention in the environment of every other creature on the planet, simultaneously caring and self-serving, preservational and catastrophic.

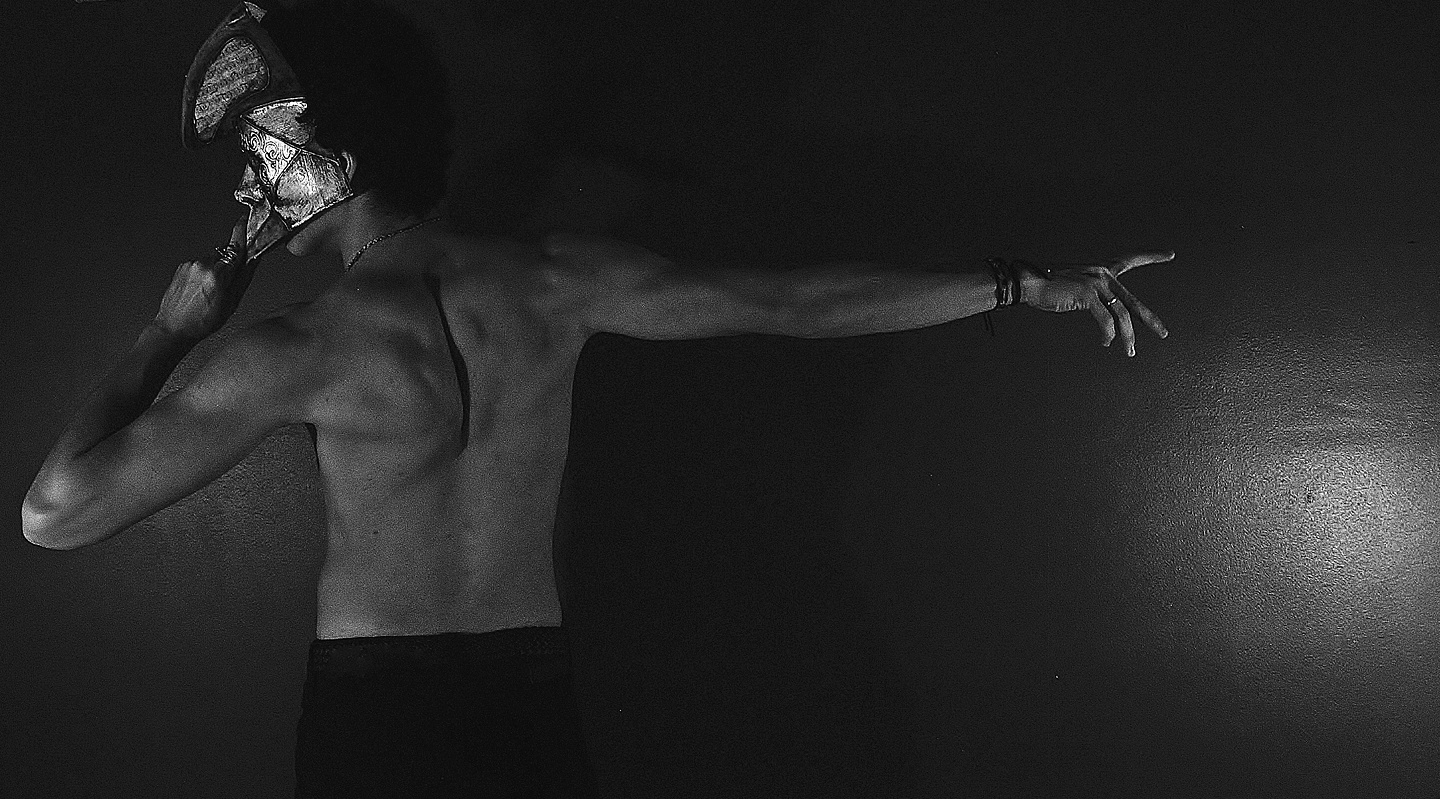

But the human animal is also distinguished by its proclivity to wear masks, literally and figuratively—a desire that is archaic and manifested in complex institutions over a vast range of cultural traditions. Masking is a form of deceit, plainly speaking, before we get to all the sophisticated elements that lead to discussions of impersonation, theatricality, or mythical performativity. At the basic level, it is a way to deceive others as to oneself, even while provisionally suspending the very mechanism of determining a self. One might say that masking oneself is in fact a gesture of self-deception, even while it presumes to deceive the other. In his book The Folly of Fools (2011), the eminent biologist Robert Trivers goes so far as to argue that natural selection favors masking oneself and that deceit and self-deception, for all the havoc they presumably unleash on environmental stability, may be endemic to living being—human-being, for sure. A straightforward interaction between stable and self-assured identities is an illusion. Even when held onto with desperation or projected forth with dogmatic violence, identities are subjected to a barrage of subversive dissimulation by the very terms of society around them. In this regard, masks profess a gesture of relief. Their denial is the most transparent confirmation of their existence. When politicians declare with aplomb that “the masks have fallen,” who are they deceiving but themselves?

The horseshoe crab shell is shaped like a perfect mask, with its tail even serving as a handle in the manner of a variety of mask traditions, Venetian or Javanese, Yoruba or Siberian. During early autumn on the Atlantic coast, it’s common to find the endless sand covered with empty shells strewn with abandon, the result of these creatures molting (growing into new shell homes) or, in advanced age, dying. Such days I feel that I am gazing at a cemetery of discarded masks.