For K.G. Subramanyan, or “Mani da” as we called him

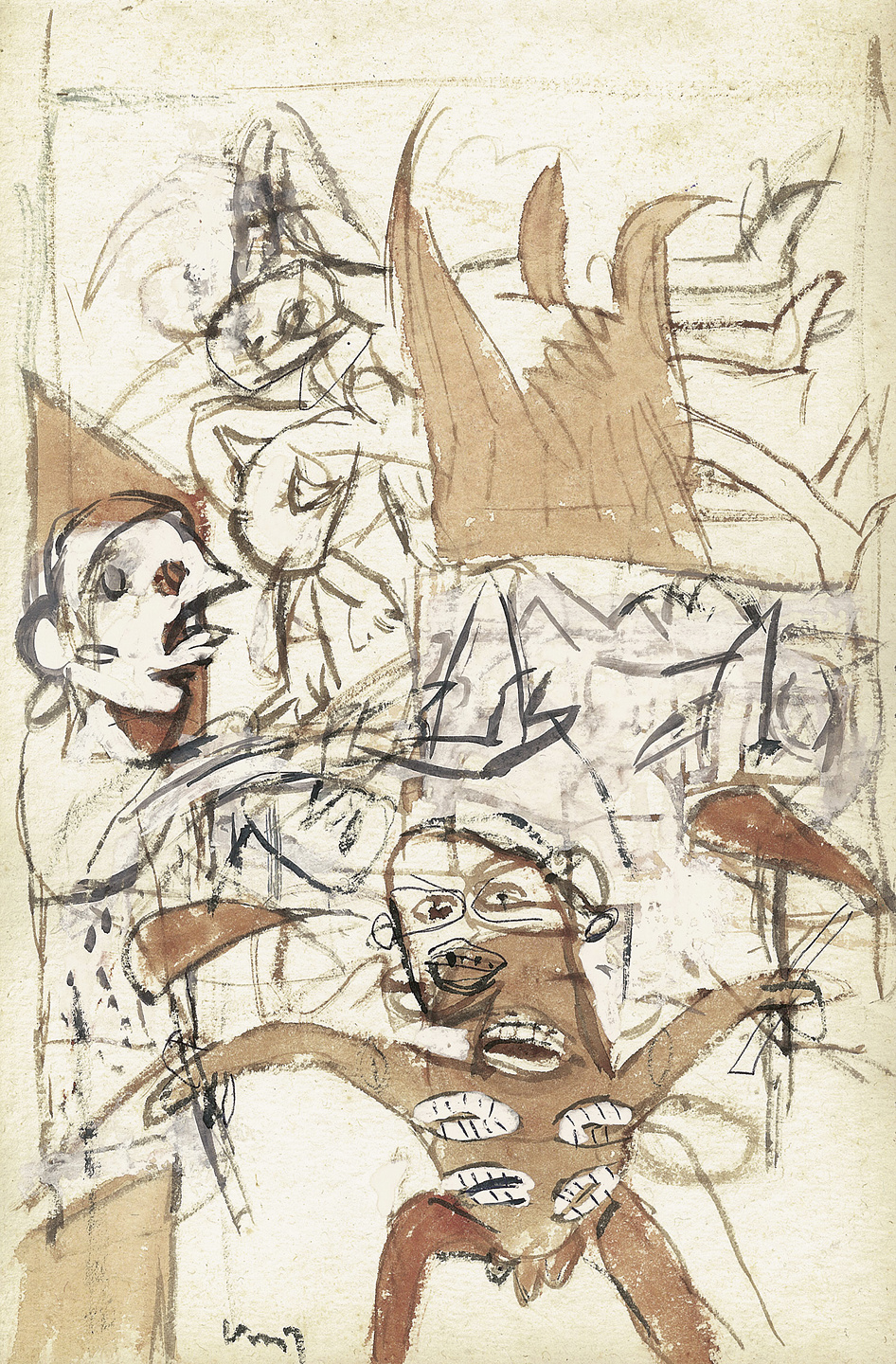

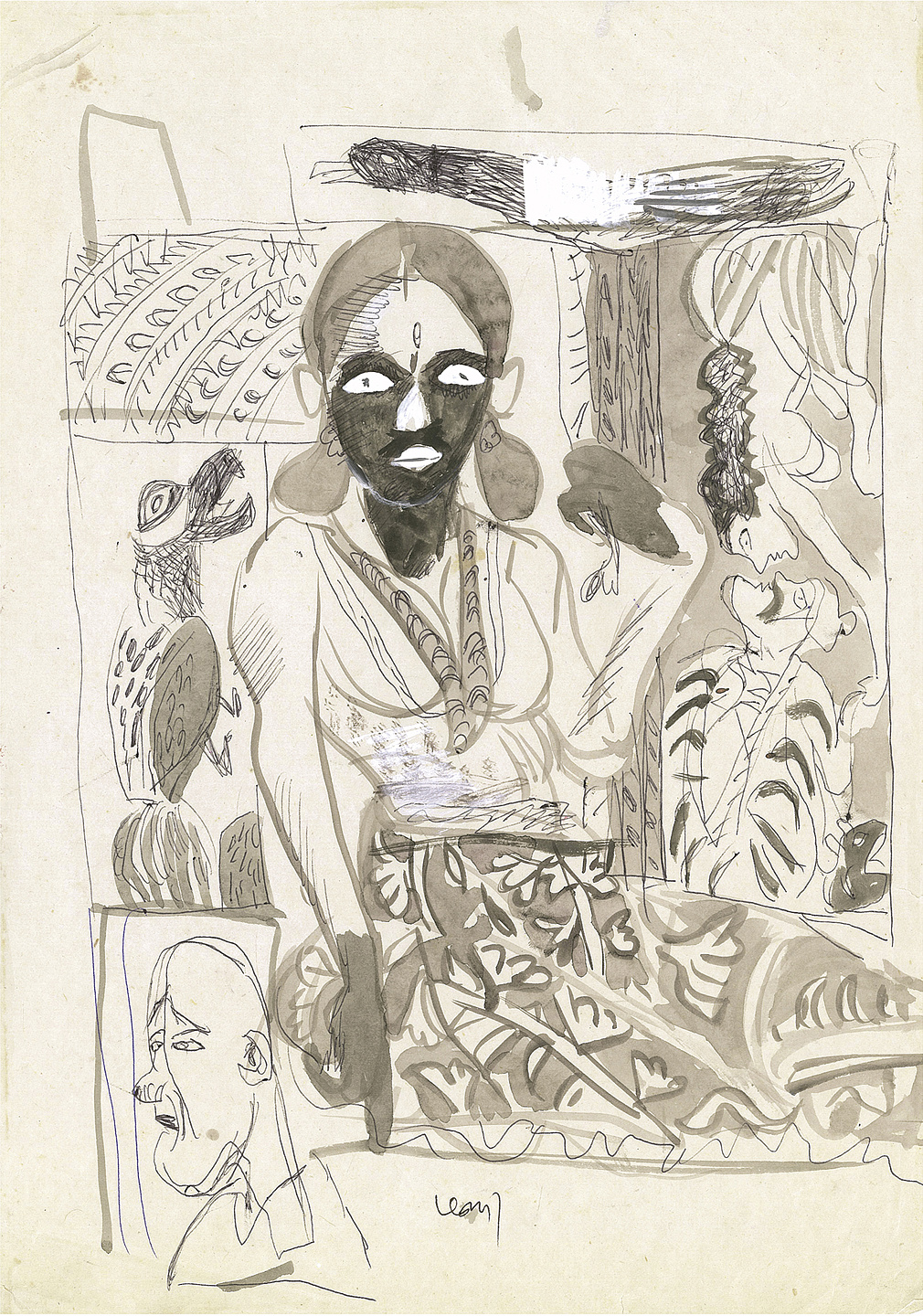

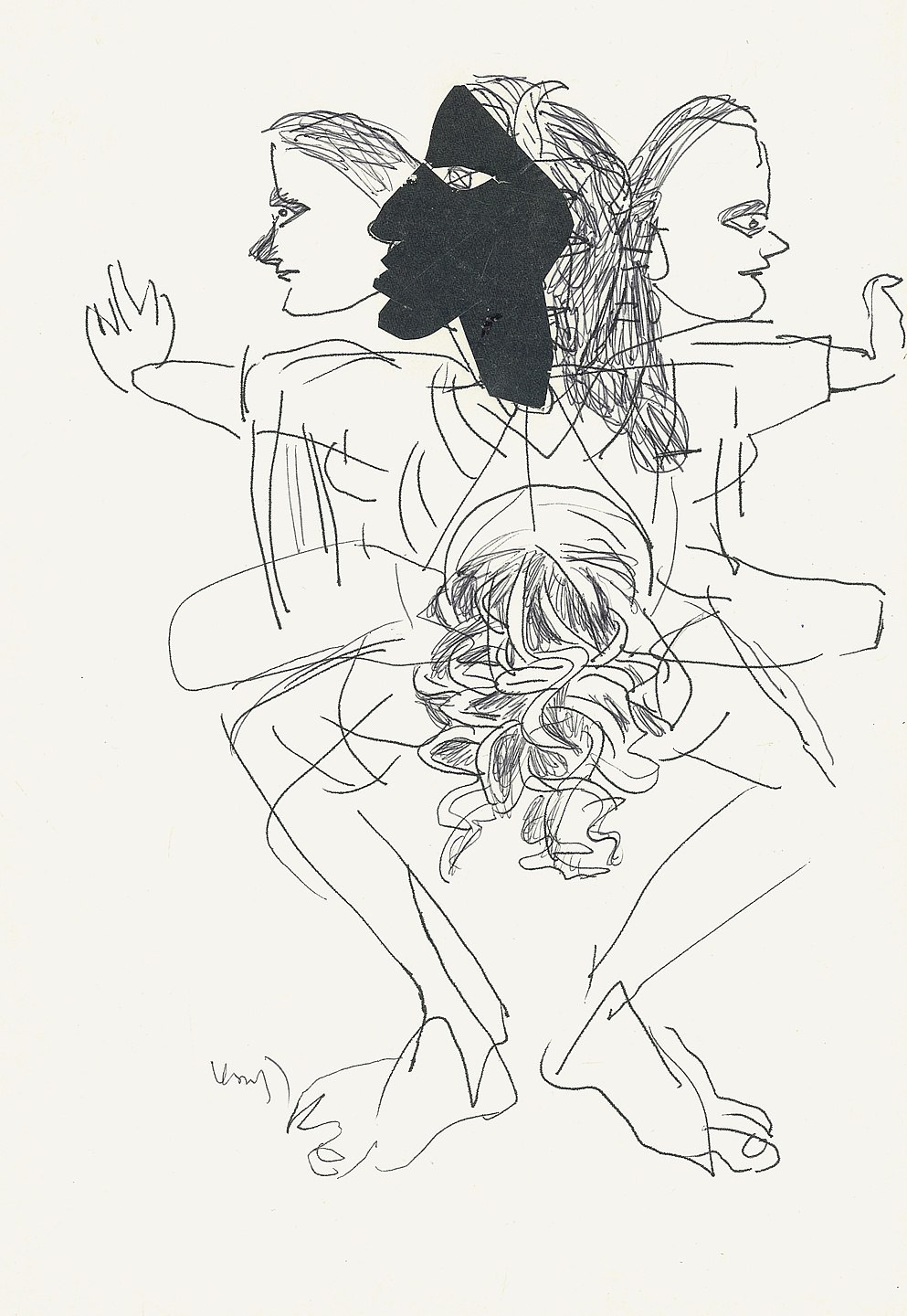

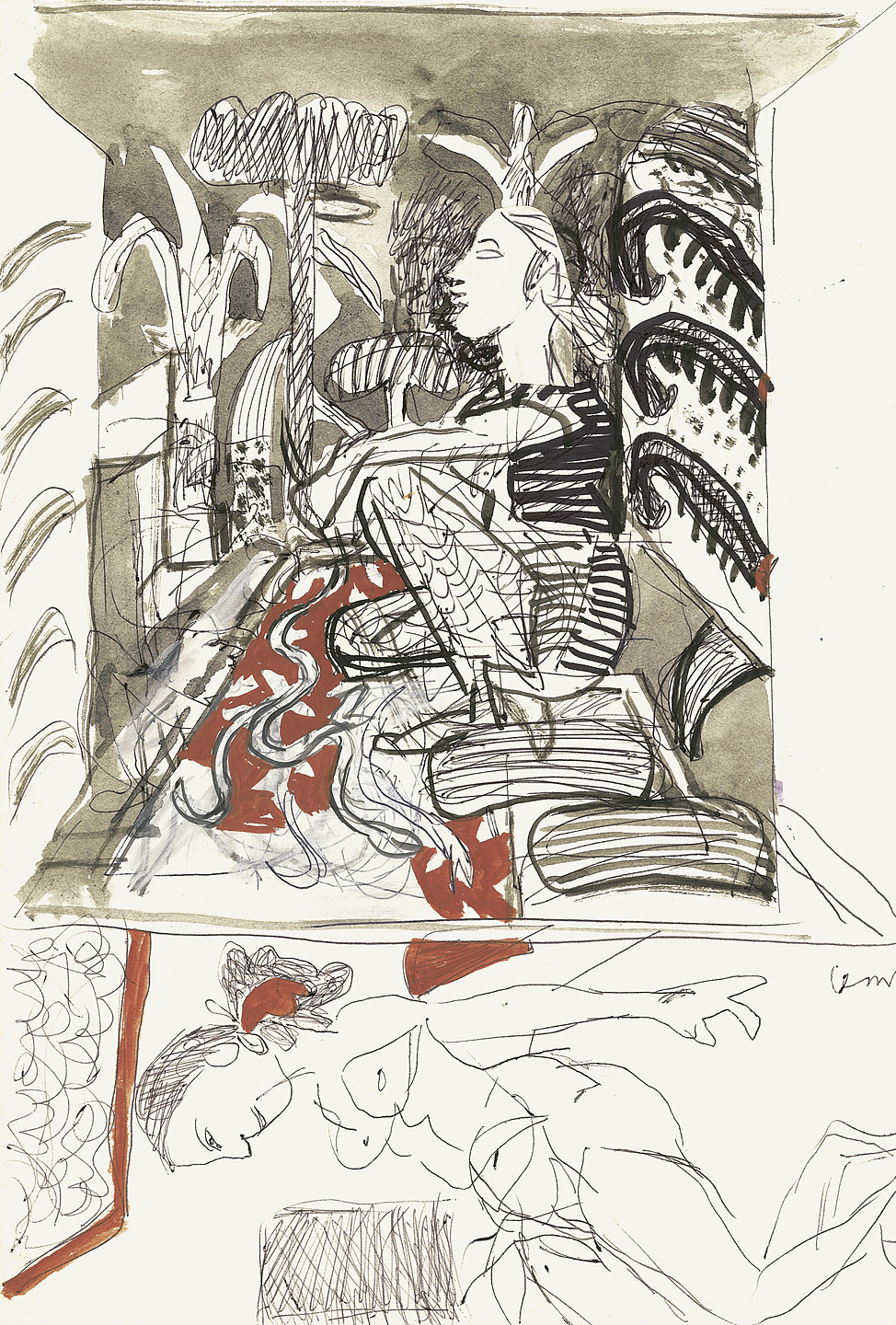

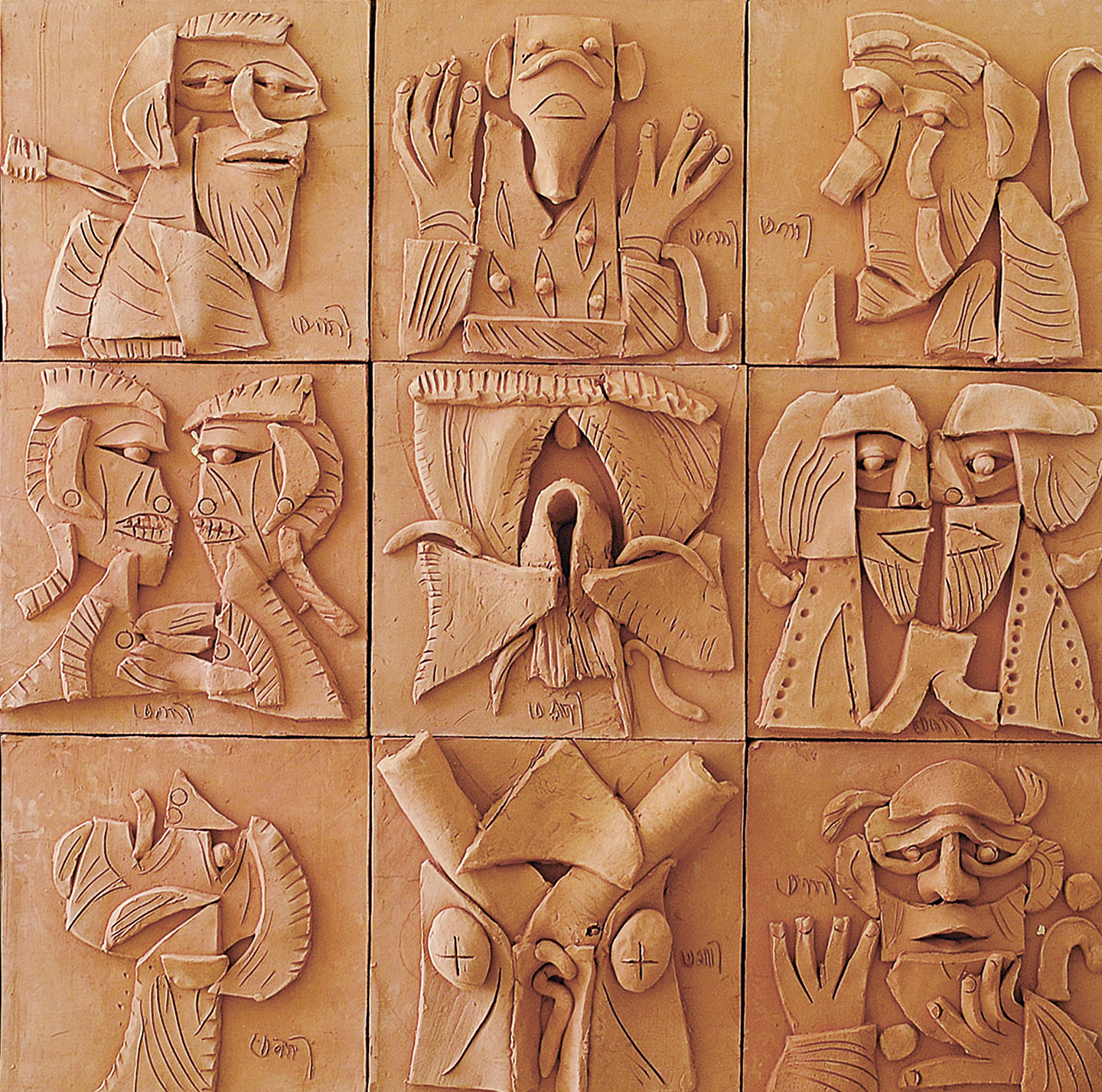

K. G. Subramanyan, Anatomy Lesson (2008, detail), terracotta, 76.2 × 76.2 cm. All works the Seagull Foundation for the Arts, Kolkata

I

Softly

like warm breath

on a cold mirroror a whisper

on bare feetwearing only white

he slipped away

unable to resist

before escapinga last glance

How many shawls from Kashmir can you give a man who never visits the mountains for his birthday? Who prefers to stay in warm climates? Year after year. Or in daring a variation by buying him fabric for kurtas, is it possible to match his sense of khadi aesthetics? I confess I did both with some degree of success, but soon found myself offering slices of my “inner self” instead, gifts that were perhaps of little material value or shape or form or weight or volume but that gestured toward personal creativity over everything else. The first attempts didn’t make much of an impression: the gifting of silver prints. Black-and-white photographs that made me proud. Met with polite acceptance. The odd smile and the comment of, “Where will I put these up?” Not as complaint but just as rueful admission from a man whose interiors were full of shelves holding books in four or five languages. The books were a failed enterprise because, after a while, between the ones I published and the ones I admired, the shelves had begun to sag. Besides, that was a gifting that took place almost daily over the years. The birthday had to be a special thing.

I began to give him pages. And pages. Of short and long poetic texts. Hesitating to use the term poetry. Or poems. This started on his eightieth birthday. His body language, on receiving these neatly printed sheaves of different kinds of paper in large colored envelopes, was welcoming. As was the quiet smile. The twinkle in the eyes would make me feel that I was on the right track. But who knows if they were read. Or liked. It wasn’t until much later, last year in fact, after twelve years of poetry, that I received comment. It came in one of his regular phone calls. Achha tum abh poet ban gaye ho: You have become a fine poet. That was it. End of praise. But not before he had rattled off the two he liked:

I

Soft like an angel’s wing

your breath upon my eyelids

as I dream shyly

of yet another autumn.Cushioning

the falling leaves.

II

Time uncertain

of how long it had been running

racing against its own shadow.Lengthening.

Then he moved on immediately: “So where does the circus go next?” A playful reference to the Sketches Scribbles Drawings exhibition that I had been traveling around the country for more than a year and a half, and which showed no signs of stopping!

He was never at a loss for words to say behind your back. Kind words. Words of affection. Words that would have made you blush with pride were they uttered in earshot. But you got tempered versions of them anyway. Through a loyal grapevine.

I would often hear, for example, “Only my dear friend Naveen is mad enough to carry large quantities of my paintings in trucks around the country. Lucknow, Bhubaneshwar, Chandigarh, Patna, Bhopal … otherwise I wouldn’t get shown all over to younger people. Mostly the paintings get shown and sold in the metro cities.”

Last week, Uma shared the last few entries written in the notebooks wrapped in brown paper. His texts echo his preoccupation with the exhibition, and must have been written a few days before his hip fracture. His surgery. His sudden passing.

In his notebooks, he writes,

When they see you working they often ask, are you working for a show? By which they mean a “sale.” For them a painting is something material, a removable object that others will pay for. Decorate their houses or offices. That a painting is a device to open up your vision and extend its reach, broaden its coverage, does not readily occur to them.

Here was a man who spent a lifetime affirming his faith in the gallery system. Working with every gallery in the country that approached him. And yet, he remained outside the marketplace. Never tempted by anything other than his muse—his art.

II

I wrote a letter to him:

September 12, 2012

Dear Mani da,

flat, obvious, ordinary, banal

How important it is to avoid being banal. Of the four deadly sins listed above perhaps this is the worst. Oh and to not realize that one is being banal is the fifth! “Ignorance” or the lack of self-knowledge. The inability to look at one’s writing and say to yourself, “This is banal.” To be satisfied with anything one writes is to be dead. Not physically. But emotionally. To me the act of writing is like playing Russian roulette with the veins in one’s wrist. Blindfolded. Slash the wrist. Let it bleed. If you are lucky you will write the “meaningful.” The edgy. As close to a truth as you can get. Or a lie. Equally effective. After all, your life’s blood is seeping out. You have little time left.

You have to do this each time you dip your pen into the blood bottle—you have to perfect the art of dying. Each time. How else will the writing read like your life depends on it?

It struck me that the same must apply to the art you create. Even more specifically, the daily gift of conversation when I visit you. I always come away refreshed and stronger. Nothing is planned or deliberate. Nothing too trivial or overtly solemn. Everything is intuitive; full of concern; relevant down to the last bit of the thabdi that we share or the Vadilal coffee ice cream. Nothing is superfluous, and yet if an onlooker were to watch us from an invisible perch they would not be able to gather from our exchanges the same philosophical truths I come away with! There is a flow that embraces both talking and silence. Without hesitation. You say things. I listen. Respond. You react. I listen. We discuss. All this is stitched together with pauses.

I am grateful for this. Deeply privileged. The way you taught, the humaneness in your teaching, is now completely lost. Teachers talk down these days. They do not “include.” Nor do they raise the students to a level where self-worth and self-assurance and, yes, self-knowledge reside. They dampen and intimidate and therefore command obedience. Not your way at all. I would go so far as to say that your every critical utterance is a blessing because it holds within it a way, a corrective measure, the possibility of doing something differently, insights into approaching one’s shortcomings in a positive sense; in other words, your teaching shows us the way forward.

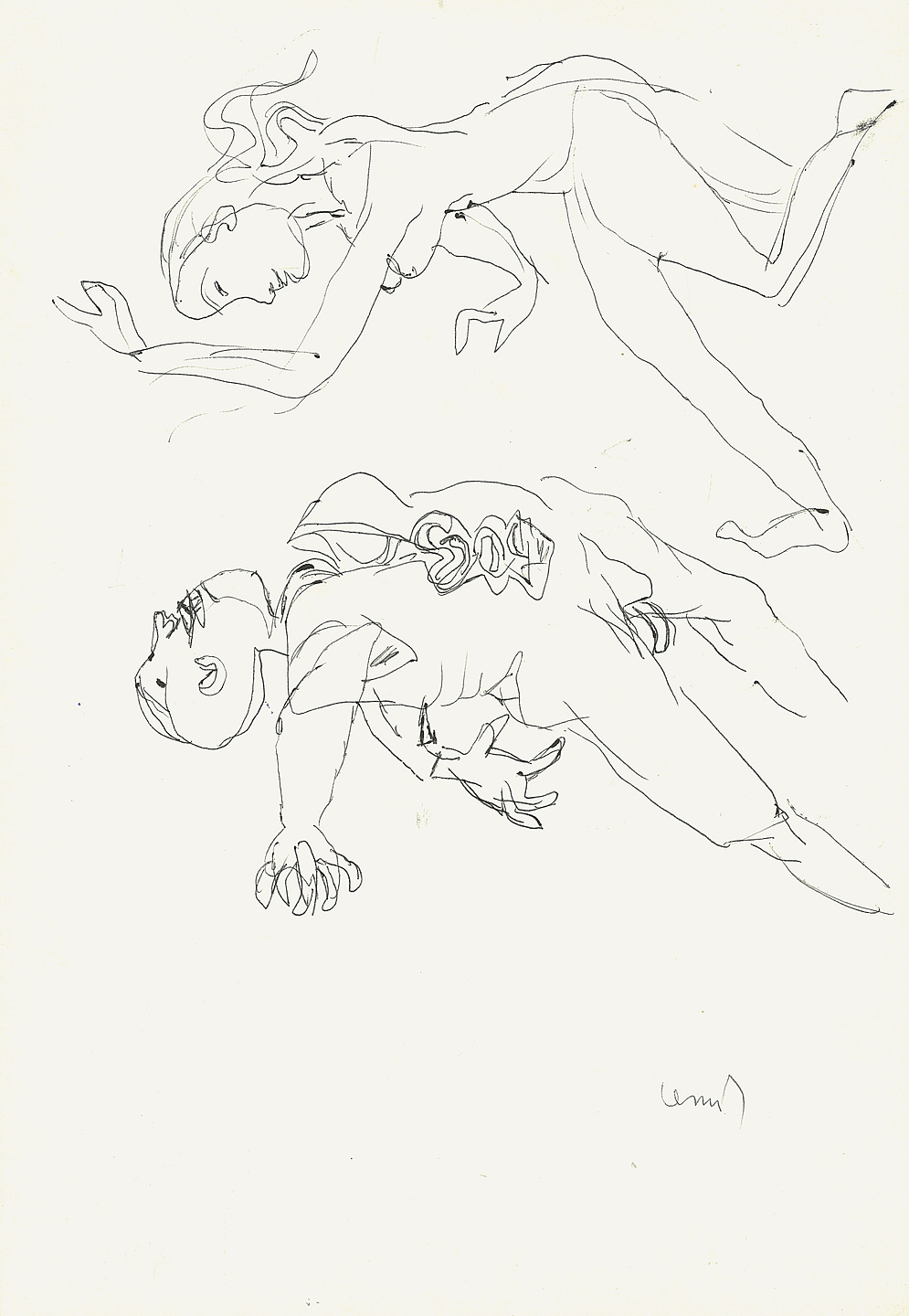

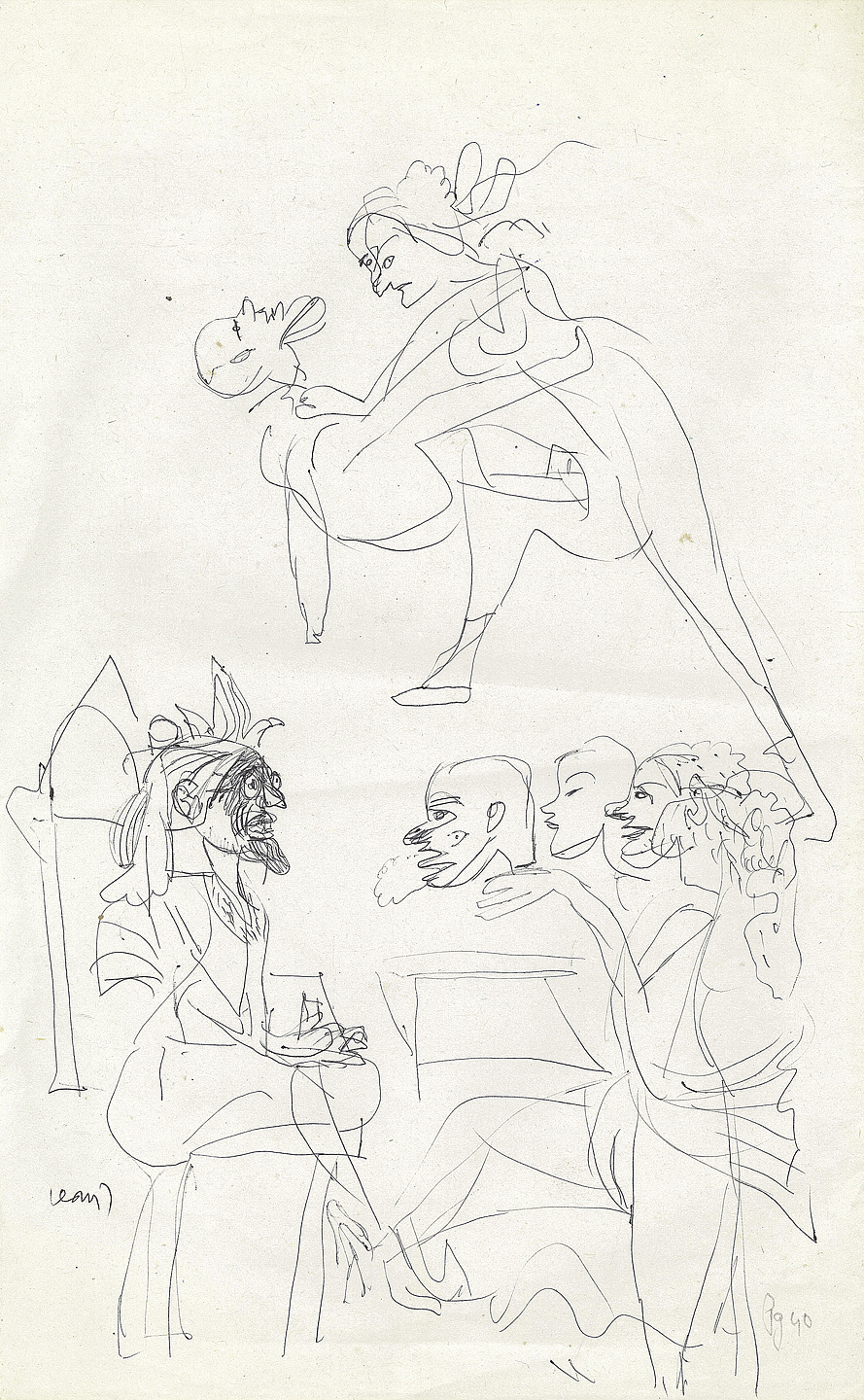

One last thing and then I will stop singing your praises for the rest of this letter! Your generous way of being. The manner in which you guess the areas of anxiety that I am often feeling or the shyness with which I hesitate to ask … or remind … or refer to … things I am brave enough to write to you about but get diffident about for fear of being pushy in your presence! I refer to the way you gently and quite casually let me know that the three Anatomy Lessons were safe and kept for me; or that you haven’t forgotten the 5 × 5 footers that I quietly but persistently keep bringing up over the last two years; or the freedom with which you allow me to plan exhibitions of your drawings … your acrylics … thank you indeed.

I am very excited with the idea of the “wall” you are planning for the art fair. And the manner of your mulling. What the young call process! And I call “the magic of making.” The twinkle with which you told the organizers that abhi time hai: It will happen if it will happen very quickly! Brought me back to my favorite exchange in one of our conversations when, replying to the question, “How long does it take to complete a painting?” you answered with yet another twinkle, “The time it takes to snap your fingers!” I wish I could express in words the sense of pleasure you emanate when sharing ideas. It must have something to do with the connection one feels with one’s child-self. Let me explain: I think our best ideas are those that appeal to the “child” within us. The wonder that resides in that part of our head and heart that has quietly and safely protected those qualities of innocence and awe that children have. A quality that never loses its sheen or luster. Because it refuses to “grow up.” Refuses to let anything other than the purely intuitive rejoice at every pleasurable idea! What a gift then to be able to summon this quality each time you create! What joy.

Thank you for your patience and with much respect and love,

Naveen

III

He wrote. Like he painted. Daily. Lucid and clear writing without the prop of artifice. Honest to its core. Finely chiseled thought. Whether it was talking about art education and the craft traditions in India or his painting:

My works have always sought to move between the real and the imaginary. True, what we call real is itself an image of a kind. My main interest was once in the passage of the objective to the abstract. Abstract to mean here an image of relative anonymity. Which allowed it a variety of interpretations. Gave it the ability to play various visual roles. Now the cross-connections I am interested in are more complicated. The images are more than visual. They have a complex identity, diverse cultural associations, and background lore. The image of Hanuman has a whole line of characters behind it. An intrepid monkey who ventures to capture the sun, who has the God of Wind as father and gets from him speed, power, agility, volatility, and the ability to change in size. Later, a staunch devotee of Rama, his emissary and worshipful vehicle. His role changing from the playful and the comic to the heroic. In a Kathakali act, he delights his audience with his monkey tricks. In an iconic painting, he flies through the air, carrying a mountain on which grow lifesaving herbs. Similarly, Durga has various versions, ranging from an elegant household deity, almost like a member of the family, to a multi-armed war goddess who rides a lion or tiger and fights and slays the buffalo demon. The lion or the tiger, even the monkey, symbolize the positive powers that fire and support our initiatives; the buffalo, on the other hand, represents a negative power or inertia. These images certainly have their origins in common scenes observed in a town or village. The vision of an able-bodied woman in a Jat village trying to control a runaway buffalo calf or a wiry Bengali villager doing the same, though with more physical skill than strength, give you two image sources for Durga. What I have an eye for are these sources, where the icon unfolds from the actual and holds within it hidden implications—of the divinities inherent in human beings and their powers. And the need of the human being to be constantly aware of the conflict between benevolent and malevolent forces, the angel and the demon, within himself.

He also wrote as a response to the times, that you and I call “political” or “cause driven.” Through many decades of practicing his art and the art of being an involved human being and artist, he allowed himself to be deeply affected by the unfolding of the times and events around him, whether these were in our country or elsewhere.

I think our response to events should come out of a deeply felt emotional reaction, which ties up, in turn, with earlier experiences or reactions. Like Picasso’s Guernica that moves from his response to the brutality of the bullfight to his response to war. I could at one time move in some of my terracotta reliefs, from my response to the devastation of a flood to my response to the brutalities of the war in Bangladesh, which eventually led to its liberation. Trying to underline the fact that the massacre of a group of human beings and their body count became marks of achievement for another group. But this can come about only when an outside event is perceived as an assault on one’s being. Superficial topicality and didacticism is something I choose to keep away from.

There are many things happening in this world that force you to react against them and to be an activist, to speak against them or take other measures depending upon your competence and ability. Just painting against them is a poor gesture. I do not however disapprove of those who do. My choice is to be an artist activist—not an activist artist.

And later, in his last televised interview, on his ninetieth birthday, he said:

There are many things in our lives that throw us into a state of anger. There are many things in our environment that irritate us. There are around us various social pressures we want to rebel against. Our lives are hemmed in with restrictions and frustrations of various kinds. In this over-inhabited world, there are various conflicts of interests that cannot be fully resolved. Administrators, social scientists, philosophers, priests—they all try in their own ways to contain the conflicts. But the best incentive for civilized living can come only from loving the world. This alone will force everyone to live in peace, to care for the environment like it was a common park.

I remember hearing in my childhood a prayer my father used to sing. It had a line that went: “Lord, let each day of mine be a festival, a celebration.”

IV

In the brown-paper-covered notebooks, we found some more thoughts and what may well be his last unfinished poems:

I

To fully appreciate a work of art or enjoy a poem you should have a surprise meeting with it. There it is all dressed to impress. And you are open to being overwhelmed.II

Our responses to works of art or literature can be of various kinds—to start with a surface relationship; sliding over it to keep up your senses. Then an encounter with its details, its context, story, its style. Then the discovery of a special feature that lifts you up into a new horizon: like a tower.III

A salt white sun

sprinkled

with pins of pepper

floating

floating with the smells

of an early springBut the days are burning hot

IV

There is the old man who sits under the peepal tree

And my response, which he will not read:

Gathering all the dust-filled afternoons of a lifetime into this single line of a poem not yet complete

I stepped into the twilight