A Reading That Loves

The Distance between V and W

Objects in Diaspora

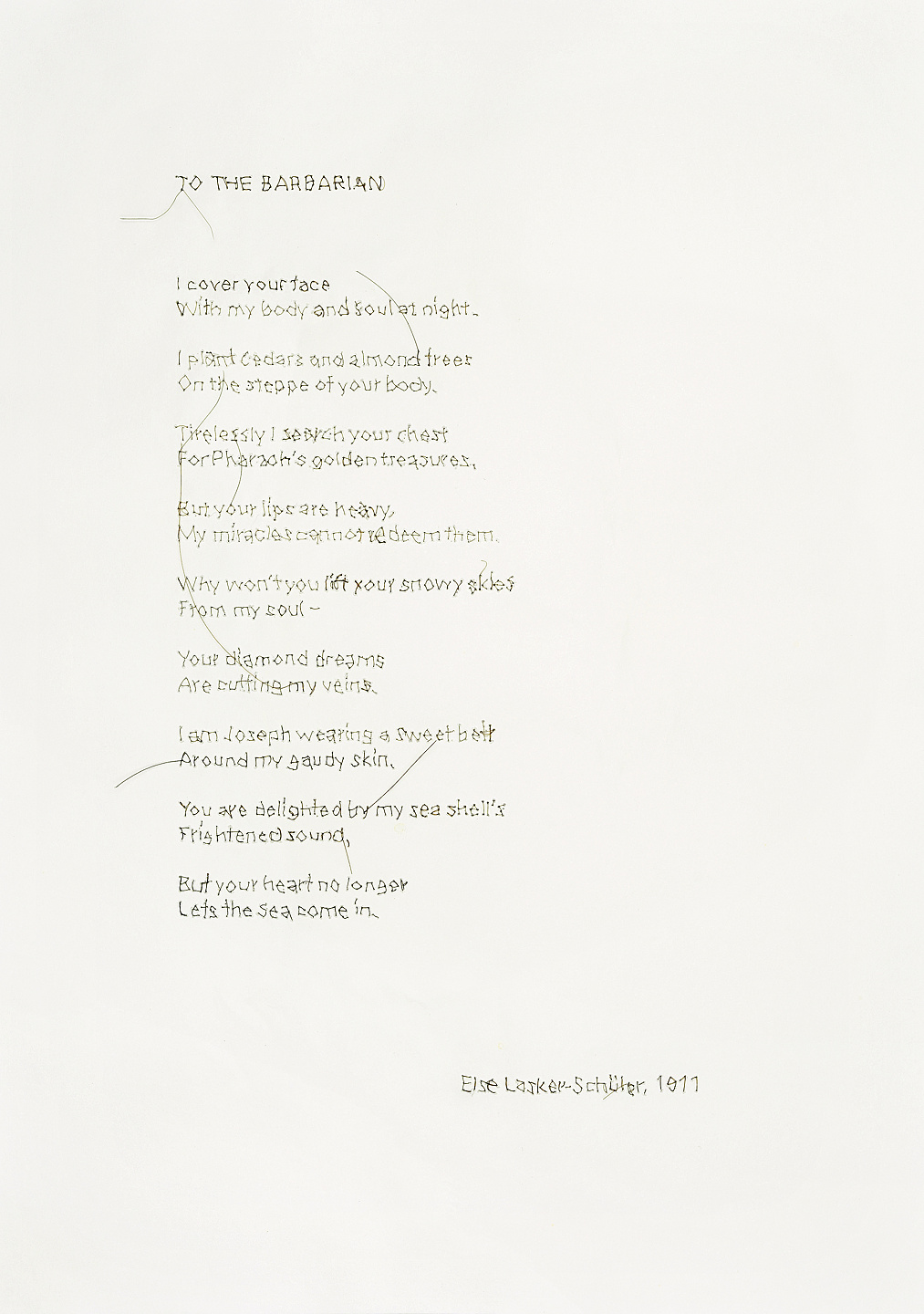

Yael Davids, To the Barbarian (2017), poem by Else Lasker-Schüler (1911) hand sewn with the artist’s hair on A4 paper, 29.7 × 21 cm. All works details from A Reading That Loves—A Physical Act (2017)

I begin with—

Our tiny house in the kibbutz. A narrow wooden door with a small window above it, separating the kitchen from the toilet.

On the day when this small window was broken, my father lifted my eldest sister up in the air, so that her head poked through the wooden window frame—her face peeking in at my mother who was inside. My mother kept calling at him to stop, but my father, who was amused by the situation, kept on poking my sister’s head through the empty window frame. All of a sudden my mother burst her way out of the toilet, her rage, its distance, immeasurable. Shouting and screaming at my father, she threw a pile of dinner plates one by one on the floor. The plates broke with an ear-splitting crack; the floor was covered by shards of glass, and my eldest sister and I were so frightened we began to cry loudly.

An unbridgeable gap between my father’s and my mother’s temperaments had opened up.

A cut.

A gesture within space.

A family.

A performance.

A floor.

As a child I feared the rage of my mother and the message concealed within it. Later the nature of such rage preoccupied me. A rage that cuts through generations. My mother’s rage was not her rage alone. It was a gender rage, a race rage, and, at times, a love rage.

Sealed memories that turn into pain. A body that is destined to speak and cry for others. To pass on this cry, these memories, wounds, and histories, to other bodies.

I have been preoccupied with the idea of proximity and distance for a while now. I keep dwelling on the immeasurable distance hidden within what presents as proximity and on the effect of such hidden distances. Think, for example, of the distance between Ramallah and Jerusalem. On the map, it is a journey of just twenty minutes by car. In reality, the distance can be much greater. For a Palestinian citizen, you have to take into consideration the many checkpoints that have to be passed, the permits to be applied for, along with the many other obstacles that have to be somehow overcome. Distances of this kind are not geographical distances, as they cannot be measured in kilometers, but in energy and emotions, such as stress, anxiety, and humiliation, and in substances, such as time, sweat, and tears.

Israel has brought about a situation where even destinations that are not far away are felt to be so. Traveling is experienced as an enclosure. Barriers to movement become an instrument of control, a means of destroying and exhausting the Palestinians who are not allowed to move in a normal fashion. Movement entails a path to normality, but also to sanity; when this mobility is constrained, a negative movement inward takes place. Subjecting people to the experience of long distances in bad conditions is often used as a political or military strategy. Death marches are an example of this. In such marches the destination is itself a very long distance, a distance that cannot be covered by the human body, by walking.

Israel has created two kinds of roads in the West Bank. One is exclusively for the use of Israeli citizens—the apartheid way—who are offered a sophisticated net of highways that has been built above the ground, stretching directly from A to B. Below, on the ground—for the use of Palestinians—is a monstrous, complicated net of dusty, unpaved roads where it is impossible to move directly from A to B. Here the notion of visibility and accessibility is clearly and deliberately linked to power. One road network is visible from afar, up in the air, radiating over the other shadowed paths.

In Paris I led a reading group. A participant in this group, Farida Gillot, recalled our reading of Édouard Glissant when she heard me describe these two types of West Bank roads, the one being new and clean and high in the air, and the other being situated deep down beneath it, tortuous and dirty. Such infrastructure reminded Farida of Glissant’s depiction of the abyss that opened up to native Africans on their passage to America. Heading to a place far away, they traveled across a vast and deep ocean in the holds of slave ships—those watery chasms, that abyss.

Glissant describes a kind of traveling that is experienced as depth rather than distance. The shape of the slave boats with their huge “bellies”—immense containers that were so unfamiliar to the native Africans who were trapped and transported inside them. Glissant writes: “First, the time you fell into the belly of the boat. … Yet, the belly of this boat dissolves you, precipitates you into a nonworld from which you cry out. This boat is a womb, a womb abyss. … This boat: pregnant with as many dead as living under sentence of death.”

Another abyss is that of the unlimited depth of the sea, the depth that slaves experienced when they were cast out into the water, weighed down with balls and chains, in order to lighten the ships when necessary.

Glissant gives different colors and shades to the abyss:

“dark shadow”

“the swirling red of mounting to the deck”

“the black sun on the horizon, vertigo”

“the green splendor of the sea”

“a pale murmur”

“the violet belly of the ocean depths”

“blue savannas of memory or imagination”

“the white wind of the abyss”

▪

In the documentary film Fuocoammare (Fire at Sea, 2016), directed by Gianfranco Rosi, the protagonist, Doctor Pietro Bartolo, looks at his computer and points to an image of a rusty boat in the sea crowded with (what we have learned to recognize as) refugees.1 Bartolo recounts:

There were 840 on this boat. There were the ones in the first class. They were outside. They paid $1,500. Then there were those in second class. Here in the middle. They paid $1,000. Then, I didn’t know this. Down in the hold there were so many. They paid $800. They were the third class. When I got them ashore there was no end for them. No end. Hundreds of women and children were in bad shape. Especially in the hold, were in bad shape. Especially in the hold. They’d been at the sea for seven days. They were dehydrated. Malnourished. Exhausted. I brought sixty-eight to the emergency room. They were in bad shape. This is a young boy all covered in burns. He’s very young—fourteen, fifteen at the most. We see so many of these. They’re chemical burns. From the fuel. They put them on unsound runner boats, and during the journey they have to fill jerry cans with fuel. The fuel spills onto the floor and mixes with seawater, then their clothes get soaked, and this mixture is harmful. It causes these very serious burns that give us a hard time and give us a lot of work to do and unfortunately leave marks that can be fatal. There. It’s the duty of every human being. If you’re human. To help these people. When we succeed we’re happy. We’re glad we could help them out. At times, unfortunately, it’s not possible. So, I have to witness awful things: dead bodies, children. On these occasions I am forced to do the thing I hate most: examining cadavers. I’ve done so many. Maybe too many. Many of my colleagues say: “You’ve seen so many … you’re used to it.” It’s not true. How can you get used to seeing dead children? Pregnant women. Women who’ve given birth on sinking boats. Umbilical cords still attached. You put them in the bags. Coffins. You have to take samples. You have to cut off a finger or a rib. You have to cut the ear off a child. Even after death. Another affront. But it has to be done. So I do it. All this leaves you so angry. It leaves you with emptiness in your gut. A hole. It makes you think. Dream about them. There are the nightmares I relive often … Often.

Some geographical distances become infinite, a chasm or abyss in one’s awareness, an understanding of how the political determines one’s personal life.

▪

Returning—

The Zionistic project claimed the right of return to—

The return to the land, the return to the history, the return to the roots, the return to singularity, the return to sovereignty. I think of this movement coming from all different geographical points, flowing toward one point: Palestine. An arrow hits a mirror, breaks the surface. Palestine was broken; Palestinian citizens were sent away, scattered in camps. A reverse movement of the Zionist project—while the Zionists returned, and settled in one territory, they eventually sent the others away, deporting, displacing, dispersing.

Nuseirat, Beach, Bureij, Deir el-Balah, Jabalia, Khan Yunis, Maghazi, Rafah, Tulkarm, Shuafat, Nur Shams, Fawwar, Jalazone, Far’a, Ein as-Sultan, Dheishen, Deir ‘Ammar, Camp no. 1, Beit Jibrin, Balata, Askar, Arroub, Am´ari, Aqbat Jabr, Homs, Ein el Tal, Hama, Jaramana, Khan Dunoun, Latakia, Khan Eshieh, Neirab, Qabr Essit, Sbeineh, Yarmouk, Dera´a, Ein El Hilweh, Wavel, Shatila, Nahr el-Bared, Rashidieh, Mieh Mieh, Mar Elias, El Buss, Dbayeh, Burj Shemali, Beddawi, Burj Barajneh, Zarqa, Talbieh, Marka, Souf, Jerash, Jabal el-Hussein, Ibrid, Baqa’a, Husn, Amman New Camp.

Refugee camps.

Refugee

Camps

Signifiers of transience. In reality they are fixed places, sealed away from our eyes. Most of the Palestinian residents in the numerous refugee camps in which they have been displaced live in difficult conditions, deprived of elementary citizen and human rights. Confined together.

If I forget you, Jerusalem,

may my right hand forget,

may my tongue stick to my palate,

if I do not remember you

The destruction of the old Jewish state is linked to the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem, which marks the first traumatic exile of the Jews to Babylonia (6th–5th centuries BCE). Significant biblical literature was created during this period of exile. It expresses a constant lament mixed with desire for revenge, repentance, and a yearning to be reconciled with God and restored to the land of Judah. It has turned the land into a beloved subject, a desired object.

This biblical literature documents a specific mood in Judaism that later supported Zionism and its claim to the right of return.2 This returning to Zion implied that the land was a vessel for the people and that the nation-state was a whole that justified the hermetic sense of borders and territories and, at the same time, the right to “take back” land that belonged to this wholeness.3

Chattel—An item that is of tangible movable or immovable property not attached to land. In Hebrew, “chattel” is metaltelim, which derives from the verb tiltel, meaning to move or shake. A word that carries a metal sound of shuddering and vibrating.

Object—In Hebrew it is chefets, deriving from the verb chafatz, meaning to desire or want.

Thing, object—In Hebrew it is etzem, a synonym for the word “bone.” Etzem, bone, is an essence, the hard matter of the body, the structure that carries. It calls for different terms from the Kabbalah, such as matter, form of matter, and abstract form.

Here we encounter the idea that the illuminations, the divine sparks, can appear in the object world in the form of language.

I believe that another aspect of the complexity of the object world has to do with the biblical commandment “Thou shalt not make unto thee a graven image.” I remember the sense of disillusionment I experienced as a child as I wandered through the Jewish section of a museum, or in visiting Jewish museums: all objects, no colorful paintings, no sculptures. Later I learned to appreciate the abstraction of thought and the care and precision given to the decoration of objects. As a child I experienced a similar disappointment with regard to the dim and dull Jewish tradition of leaving stones on graves. I remember the sense of enlightenment I felt when my mother explained to me that the reason one leaves stones on graves, and not flowers, is that stones belong to the inanimate world (Olam Ha Atzamim). Stones leave the dead in peace, whereas flowers call them to life.

Different words for object in Hebrew suggest more than an artifact—movement, desire, essence, and illuminations.

In 2015, the Israeli National Library won a long-running trial (lasting thirty-nine years) against the two daughters of Esther Hoffe. The dispute was over several boxes of Franz Kafka’s original writings and drafts of his published works. Kafka left his published and unpublished works to Max Brod, along with explicit instructions that the work should be destroyed upon Kafka’s death.

Brod did not honor Kafka’s request and did indeed publish a few of his works. In 1939 Brod escaped Nazi-occupied Prague for Palestine. Though many of the manuscripts under his guardianship were placed in the Bodleian Library in Oxford, Brod still owned a large number of them until his death in 1968. He left the manuscripts to his secretary, Esther Hoffe, who appears to have been his mistress. Esther kept and guarded most of the Kafka manuscripts until her death, except for the manuscript of The Trial, which she sold for two million dollars. At that point it became clear that one could make quite a profit from Kafka. After Esther Hoffe’s death, her daughters, Eva and Ruth, who inherited the rest of Kafka’s writings, put the works up for sale, claiming that the value of the manuscripts should be determined by their weight—quite literally by what they weighed. As one of the lawyers representing Hoffe’s estate stated: “If we get an agreement, the material will be offered for sale as a single entity, in one package. It will be sold by weight. … So there is a kilogram of papers here, the highest bidder will be able to approach and see what’s there.”

Thus Kafka—or his writings—was turned into an object of negotiation, and his work into a chattel. In the trial there were two main parties seeking to acquire the work either by claiming the right to it, as the National Library of Israel did, or by offering to buy it, as the German Literature Archive in Marbach did. The National Library of Israel argued that Kafka’s writings were not a commodity but a “public good” belonging to the Jewish people. Kafka is claimed to be a primarily Jewish writer, and his writings are counted among the cultural assets of the Jewish people. What is interesting to emphasize here is the presumption that the State of Israel represents the Jewish people. This claim overlooks the distinction between the Jews who are Zionists and the Jews who are not, such as Jews living in the Diaspora. It marks the Zionistic assumption that Galut is a state of exile and despondency that should and can only be reversed through a return to Israel. Zionism errs in thinking that exile must be overcome through an appeal to the Law of Return.

The German Literature Archive in Marbach argued, by contrast, that Kafka belongs to the German literary tradition and specifically to the German language. Here it seems as if the Germans were transcending citizenship for the higher order of language—in other words, by shifting nationalism to the German language itself. This argument erases the significance of multilingualism in Kafka’s writings. Some scholars believed that Marbach would have been the proper home for Kafka’s writings, since this library already owns the largest collection of his manuscripts in the world. Yet Philip Roth described the German claim for Kafka’s writings as “yet another lurid Kafkaesque irony … perpetrated on twentieth-century Western culture,” observing not only that Kafka was not German but that his three sisters perished in Nazi death camps.

Inspired by Judith Butler’s reading of and text on The Trial, my main concern here is with Kafka’s views on Zionism and his general view on reaching and failing to reach a destination through his writing. Analyzing Kafka’s work, Butler asks: “What would it mean to be freed of the spatiotemporal conditions of the ‘here?’ … Kafka’s journeys are into the infinite, that will gesture towards another world.” And gesture, Butler continues, “is the term that Benjamin and Adorno use to talk about these stilled moments, these utterances that are not quite actions, that freeze or congeal in their thwarted and incomplete condition. … A gesture opens up a horizon as a goal, but there is no actual departure and there is surely no actual arrival.”

Kafka’s work expresses the poetics of the nonarrival. Butler concludes that Kafka’s writings open up an infinite distance between the one place and the other—and in so doing constitute a non-Zionistic theological gesture.

To Israel, the fact that Brod was a Zionist seems more valuable than the fact that Kafka was not; he never traveled to Palestine and never really planned to. There is no doubt that Kafka’s Jewishness was important to him, but it definitely does not imply any sustained view on Zionism. For me, Kafka’s writing is an affirmation of the fragility of being in a place that is not supported by a territory. In most of Kafka’s works, messages do not arrive at their destination; commands are misunderstood and so goals perpetually fail to be reached. Kafka performs in the space between unfulfilled destiny and the intention of reaching it. Kafka’s writings express the spirit of being an exile, also from a linguistic point of view; the idea of entering language from its exterior is a point made by Deleuze and Guattari in their essay “Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature.”

Nevertheless: At the end of a thirty-nine-year trial, the National Library of Israel has won. Kafka now belongs to the State of Israel; Kafka has turned into a belonging.

Kafka’s writings are spoken about in the monumental correspondence between Walter Benjamin and Gershom Scholem. Their correspondence expresses a bond between two significant Jewish intellectuals. I will take the risk of politicizing it by putting it in a vulgarly bare manner: One—Gershom Scholem—was a Zionist soul who emigrated in 1923 to the British Mandate of Palestine. Scholem was a great scholar of Judaica and Kabbalah and an active figure both at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and the National Library of Israel. The other—Walter Benjamin—had the soul of a Jewish refugee, of an exile. Benjamin was a constant refugee from the National Socialist regime, and yet he kept delaying a trip to Palestine. The beauty of the correspondence between these two souls is the experience of an intellectual discourse that develops into love and affection inside the darker times of their shared history. Their great love of books, and books as such, builds a bridge between these two very different men and their existential states, overcoming the geographic and ideological distance between them; a distance that is constantly changing according to Benjamin’s next escape route. Here books and thoughts turn into experience, an experience of affection and compassion—bridge-building.

The intellectual passion and desire of the two “meet” when they exchange thoughts around Kafka’s writings. I find this point the most touching. As Benjamin wrote of Kafka: “No other writer has obeyed the commandment ‘Thou shalt not make unto thee a graven image’ so faithfully.” Benjamin drew strength from Kafka’s writings in both an acute historical and personal sense. Benjamin found asylum in Kafka.

Kafka turned into a home, into a land with no territory, a land that is a horizon.

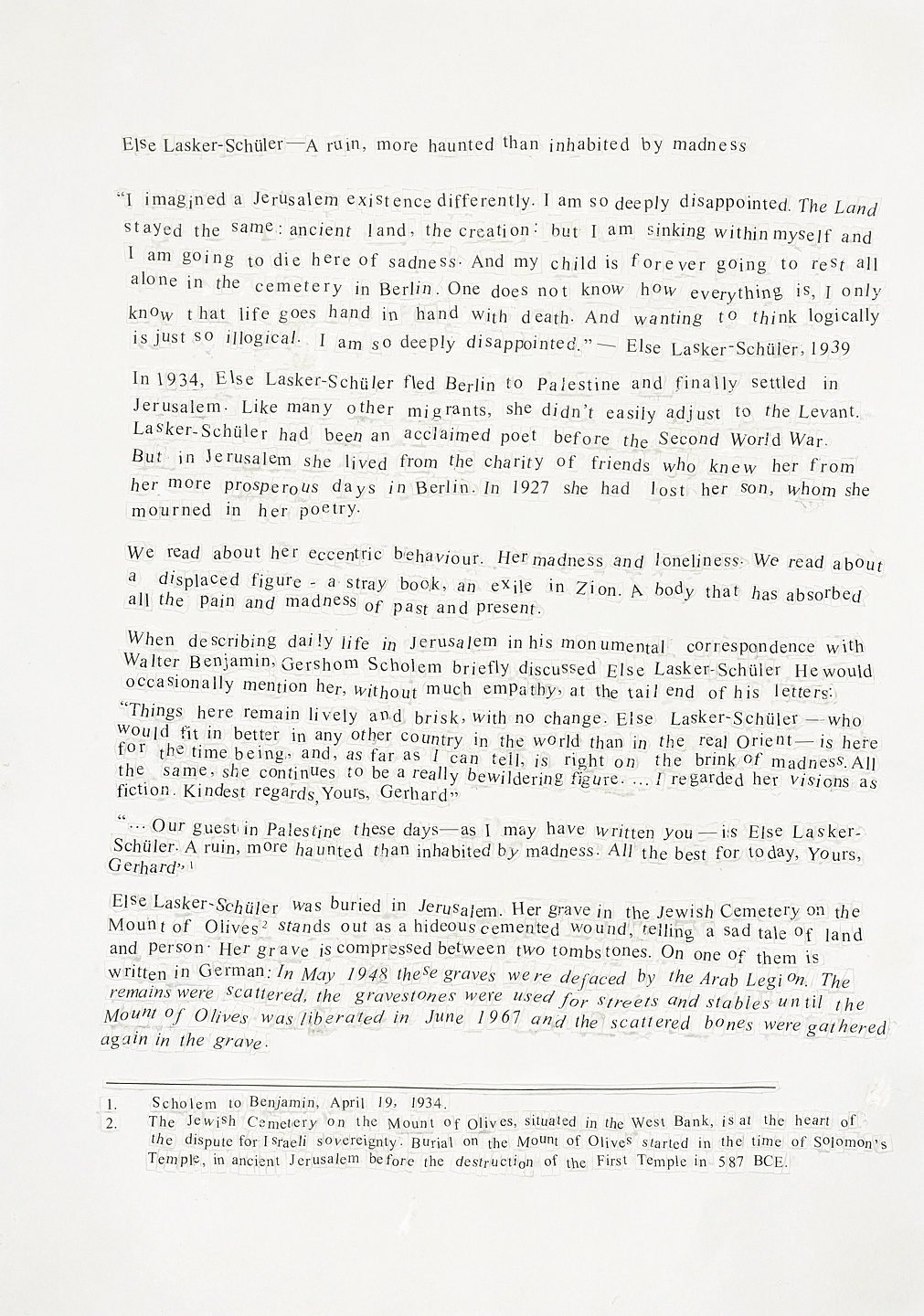

Another writer whom Gershom Scholem discussed briefly in his correspondence with Benjamin, when describing daily life in Jerusalem, was Else Lasker-Schüler. He would occasionally mention her, without much empathy, at the tail end of his letters:

Things here [in Palestine] remain lively and brisk, with no change. Else Lasker-Schüler—who would fit in better in any other country in the world than in the real Orient—is here for the time being, and, as far as I can tell, is right on the brink of madness. All the same, she continues to be a really bewildering figure. … I regarded her visions as fiction. Kindest regards, Yours, Gerhard

Our latest guest in Palestine these days—as I may have written you—is Else Lasker-Schüler. A ruin, more haunted than inhabited by madness.

All the best for today, Yours, Gerhard4

In 1934, Else Lasker-Schüler fled Berlin for Palestine, finally settling in Jerusalem, as most German-Jewish intellectual refugees did at the time. Like many other migrants she could not adjust to the Levant. Before World War II, Lasker-Schüler had been an acclaimed poet. But in Jerusalem she lived from the charity of friends who had known her since her more prosperous days in Berlin.5 In 1927 she had lost her son Paul, whom she mourned in her poetry. She wrote of her exile:

I imagined a Jerusalem existence differently. I am so deeply disappointed. The land stayed the same: ancient land, the creation; but I am sinking within myself and I am going to die here of sadness. And my child is forever going to rest all alone in the cemetery in Berlin. One does not know how everything is, I only know that life goes hand in hand with death. And wanting to think logically is just so illogical. I am so deeply disappointed.

We read about her eccentric behavior, about her madness and loneliness; we read about a displaced figure—a stray book, an exile in Zion. A body absorbed by the pain and madness of past and present.

To My ChildYou will always die again for me

With the parting year, my child,When leaves disperse

And twigs grow thin.With the red roses

You tasted death bitterly,Not a single withering throb

Was spared you.So I weep sorely, forever,

At night in my heart.Still the lullabies sigh out of me

That sobbed you into death,And my eyes turn no more

To the world;The green of leaves hurts them.

—but the Eternal lives in me—My love for you is the image

One can make oneself of God.I also saw angels in weeping,

In the wind and in the rain.They drifted ………

In a heavenly air.

When the moon’s in bloom

It resembles your life, my childAnd I cannot look

When the light-spending butterfly flutters away carefree.I never foreshadowed death

—spying around you, my child—And I love the room’s walls

Which I paint with your boyish face,The stars in this month

That fall so many sprinkling into life

Drop heavy on my heart.

Else Lasker-Schüler was buried in Jerusalem. Her grave in the Jewish Cemetery on the Mount of Olives stands out as a hideous cemented wound, telling a sad tale of land and person.6 Her grave is compressed between two tombstones. On one of them is written in German:

In May 1948, these graves were defaced by the Arab Legion. The remains were scattered, the gravestones used for streets and stables until the Mount of Olives was liberated in June 1967 and the scattered bones were collected in one grave.

I think:

He said to me, ”Son of man, can these bones live?” And I answered, ”O Lord God, You know.” Again He said to me, ”Prophesy over these bones and say to them, ‘O dry bones, hear the word of the Lord.‘” Thus says the Lord God to these bones, ”Behold, I will cause breath to enter you that you may come to life. I will put sinews on you, make flesh grow back on you, cover you with skin and put breath in you that you may come alive; and you will know that I am the Lord.”7

▪

Another letter between Scholem and Benjamin revolves around Benjamin’s library and his attempts to rescue it. Indeed, one of the torturous aspects of Benjamin’s escape was of having to leave behind his precious books. Benjamin was an avid reader and collector of books who caringly and pedantically built up a huge personal library, to which he was tremendously attached. Benjamin’s wearisome struggle to find his next sheltering place from the Nazis was as intense as his wearisome struggle to find a sheltering place for his library. Benjamin succeeded in having a small part of his library sent to Sweden, where he himself spent some time, but the greater part of his books were burned by the Nazis. Some say that he died when his library died.

A portrait of a man as a library.

The library as a man’s asylum.

The salon as a woman’s asylum.

A room is a performance. A salon. A reading that acts. A reading that loves. Inward. A room is a womb. It denies any law. A room is a shelter.

Ho Rahel, Rahel.

In eighteenth-century Berlin, Jewish women held most of the salons. These salons embodied a double emancipation: gender emancipation and ethnic emancipation.

Jewish people, who were mostly deprived of citizen rights, could enter (or buy) society by means of economic or intellectual prosperity.

Since Jewish people and in particular Jewish women had very little access to social life, the salon performed its reverse—the social entered into the Jewish woman’s room, into her cosmos. Rahel Varnhagen hosted one of the most significant salons at the time in her small attic. Varnhagen’s awareness of her excluded position was remarkable as she turned it into a form of property: “One is not free if one must represent something in the bourgeois society, a spouse, the wife of a civil servant, etc.”

Varnhagen developed her own style of salon—what people might call a more psychosocial one. Her salon was about learning to listen and talk in the language of the visitors—a sort of transparency, an innocent, “clean” way of accepting and transmitting other voices. As a writer, Varnhagen also created a new practice of writing; she did not write books per se but instead concentrated on letter writing and worked on establishing a network of people who would share this undertaking with her. She assigned her letters dates and geographical destinations. Thus her writing and being were always in relation to time and place, although as a Jewish woman she was subjected to living in a shadow realm. She was the first German-Jewish woman to describe how it feels to be imprisoned “between Pariah and Parevenu,”8 which Heinrich Heine called the “Judenschmerz.” Varnhagen called it “the text of my wounded heart.” It seems as though a sense of lack, of having neither power nor authority, contributed to her uniqueness. “Regarding the opinion that I should be a queen (not a reigning one) or a mother: I am experiencing that I am nothing. No daughter, no sister, no woman, not even a citizen.”

Echoing this statement of feeling, Elsa Lasker-Schüler told her fellow writer Martin Buber, who also lived in Jerusalem: “I am not a Zionist woman, I am not a Jewish woman, not a Christian woman; but I believe I am a human being, a very sad human being.”9

Gershom Scholem, by contrast, was a genuine Zionist, a member of Brit Shalom, a group of intellectuals who believed in a peaceful coexistence between Arabs and Jews. Scholem was a librarian at the National Library of Israel, and with a group of scholars he dedicated himself to the collection of books for the library. Fearing the annihilation of Jewish cultural and intellectual heritage by the Nazi regime, he devoted great care to forming a place for this project. In reading his correspondence, one senses Scholem’s dedication to having copies of each of Benjamin’s writings sent to Palestine.

Books and writings cross distances, are taken from, given to, carried by, cared for by, nourished by, written by, looted by, burned by.

Between May 1948 and February 1949, thirty thousand books, manuscripts, and newspapers were seized from forcibly evicted Palestinian homes of West Jerusalem, while forty thousand books were taken from urban cities such as Jaffa, Haifa, and Nazareth. Many of the books were later marked with just two letters—“AP” for abandoned property—and incorporated into Israel’s national collection, where they remain today.

We learn of the complexity of this story through the work of historian Gish Amit, who writes, “The National Library … protected the books from the war, the looting and the destruction, and from illegal trade in manuscripts. It also protected the books from the long arm of the army and government institutions.” However, while in 1950 the books were catalogued according to their owners’ surnames, since the idea was to return the books after the war, in the 1960s the names of the owners were replaced by “AP.” In this period there was a shift in attitude, and the National Library was nationalized per the political mood at the time.

The writer Hala Sakakini tells how she was permitted by the librarian of the National Library of Israel to choose only one book to look at:

We chose The Misers of al-Jāḥh.iz., an encyclopedia from the ninth century. And indeed after a while the librarian came back to us and the book was in his hands. He allowed us to leaf through the book right there and then, but only under his supervision. As though we were dangerous culture thieves he stood there watching and waiting until we gave the book back.

This book belonged to the family of Hala; it was part of the large personal library of Hala’s father, Khalil Sakakini. Sakakini, a prominent Christian-Arab teacher, writer, and intellectual, was one of the people from whose homes books were taken. On April 30, 1948, he fled his home in the Katamon neighborhood in Jerusalem.10 Eventually, he described his separation from his books in his diary: “Farewell, my chosen, inestimably dear books. I do not know what your fate has been after we left. Were you plundered? Were you burned? Were you transferred, with precious respect, to a public or private library?”

Susan Buck-Morss writes: “The ‘archive’ of a ‘living methodology’ … consists of the material remains of life stored—rescued—in libraries, museums, second-hand stores, flea markets. … The fact that only certain material objects survive, even as photographic traces, is part of their ‘truth’—from a critical-historical point of view, perhaps the most important part.”

The Zionist movement prompted a major wave of Jewish immigration from Yemen during the late 1940s and early 1950s. The Jewish Yemenis lived in remote regions and had been affected neither by the West nor by modernism. They were seen as the forgotten tribe—the “real, authentic Jews.” On the other hand, they were also seen as part of the Levant that needed to be educated, civilized, “de-Arab’d.” They were the Arab Jewish. As the Zionist enterprise was Western, the Zionists feared that the state of Israel would become infected—“contaminated”—by the Arab nature of the Yemenis (and other communities from the Levant such as Iraqis and Moroccans).

Thus as the Yemenis were gathered in camps before entering Israel, they were made to give away their books, with the promise that they would be returned once they arrived. These books were extremely valuable Torah scrolls and holy books dating back five hundred years. When the Yemenis arrived in Israel and asked for their books, diversions and excuses were provided: there was a fire in the harbor, the books have been stolen, and so on. Nevertheless, thousands of these books found their way into the National Library of Israel as well as into the state’s academic institutions and museums. Many have also been acquired by private hands, seemingly more entitled to deal, preserve, and understand such an old and valuable cultural heritage.11 These valuable scrolls and books had been used daily and kept for decades in the synagogues of Yemen—now no more.12

▪

On her deathbed my mother asked us, her three daughters, to take out of her drawer a few items, ones that up till that day we had failed to value. She told us stories about a few of the things and, in an emotional voice, the history of a tiny brooch made of silver with a small piece of ivory at its center. And there, extremely small, in fact scarcely visible, was an image of a person carried by a two-wheeled chariot. My mother’s grandfather made this jewelry. The Yemenis were great silversmiths, and Grandpa Zecharia was the silversmith of the Ottoman governor of Palestine, Djemal Pasha.

Later I learned that he died walking to Galilee during the exodus from Jaffa.13 An image of a person carried by a two-wheeled chariot—these distances that history repeatedly converts into a physical and mental torture. Routes that turned into nets, weaved carefully by militaristic brains to capture and slowly decimate the subjected objects.

And as my mother passed the brooch to us, I felt for the first time the unbearable pain of admitting that she would leave us. For the first time, I saw my mother admitting that to herself. Passing us the objects meant passing away. Passing the objects meant building a legacy that meant holding and carrying a narrative.

A cut.

An unbridged gap.

A gesture within space.

A family.

A performance.

An object.

Yael Davids, Else Lasker-Schüler—A Ruin, More Haunted Than Inhabited by Madness (2017), collage on A4 paper, 29.7 × 21 cm

Yael Davids, Else Lasker-Schüler—A Ruin, More Haunted Than Inhabited by Madness (2017), A4 paper, 29.7 × 21 cm

1 The documentary film was shot on the Sicilian island of Lampedusa, which has become the landing point for boats of refugees and migrants from Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. The film portrays the dangerous Mediterranean crossing against the backdrop of the daily life of the Sicilian islanders.

2 The Law of Return was enacted by Israel’s Parliament in 1950. The Law declares the right of Jews to come to Israel: “Every Jew has the right to come to this country as an oleh.” Those who immigrate to Israel under the Law of Return are immediately entitled to gain citizenship in Israel.

3 Zionist writing follows the line of thought that says: “Just as the Jewish people longed to return to their land, the land waited for the return of its children.” A “land without a people” was supposedly left deserted but abundant, waiting to be redeemed—thereby erasing the existence of the natives who lived in Palestine. “Waiting for a people, its people, to come and renew and rehabilitate its old home, cure its wounds … to come with the passion of pioneers, the spirit of sacrifice, enthusiasm, courage and genius, and create and build and establish a new Land of Israel” (Ben-Gurion and Ben-Zvi).

4 Gershom Scholem to Walter Benjamin, April 8 and April 19, 1934.

5 Heinz Gerling and the poet Manfred Schturmann came to her aid. Gerling opened a bank account for her and arranged for regular payments to cover her expenses, and Schturmann edited her work and helped with her dealings with publishers.

6 The Jewish Cemetery on the Mount of Olives, situated in the West Bank, is at the heart of the dispute for Israeli sovereignty. Burial on the Mount of Olives started in the time of Solomon’s Temple in ancient Jerusalem, before the destruction of the First Temple in 587 BCE.

7 Ezekiel 37: 3–6.

8 This is the title of a chapter in Hannah Arendt’s book, Rahel Varnhagen: The Life of a Jewess (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1997).

9 Sigrid Bauschinger, Else Lasker-Schüler: Biographie (Gottingen: Wallstein, 2004), p. 369.

10 Between 1947 and 1949, more than seven-hundred thousand Palestinians were expelled or fled from their homes during the Palestine war. The Palestinian exodus is known as the Nakba, or the catastrophe (النكبة, “al-Nakbah,” literally means disaster or catastrophe). Some six hundred to seven hundred Palestinian villages were destroyed while Palestine was almost entirely extinguished. At the end of the war, the State of Israel kept the area that had been recommended by the UN as well as almost 60 percent of the area allocated to the proposed Arab state. Nearly one-third of the registered Palestine refugees (more than 1.5 million individuals) continue to live in fifty-eight recognized Palestine refugee camps in Jordan, Lebanon, the Syrian Arab Republic, the Gaza Strip, and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem.

11 The Yemeni migration to Israel was shadowed in many ways—see the “stolen babies” affair. As many as five thousand Mizrahim Jewish babies, mostly Yemenis, were reported missing in Israel between 1948 and 1954. Families say they were given away but, in fact, babies were taken from their mothers directly after their birth in the hospital. When mothers asked for their babies back, they were often told that the baby had died. However, these babies had been given to Ashkenazi families to be taken care of and brought up by more “educated” families.

12 The Zionist determination to effectively erase traces of Arab culture from the Middle Eastern Jewish people was echoed in their determination to drive out the Palestinian community from what would become the State of Israel. The Zionists did not seek to merely conquer but to replace. They sought to build the Jewish state on the ruins of Arab society in Palestine. Ben-Gurion had to not only destroy Palestinian society but also ensure that “Arabness” could not creep into his new Jewish state by means of the Yemenis.

13 The Ottoman Empire feared that the Jewish community on the coastline would collaborate with the soon-to-be arriving enemy, the British Army. (Recently, however, an exchange of letters between Ahmed Djemal Pasha and Istanbul was found, which tell a different version of the story: here, Pasha was concerned for citizen security along the coastline during wartime.) The Jewish community of Tel Aviv-Jaffa (around ten thousand people) had to be deported within twenty-four hours to other areas of Palestine. Of those people, around three thousand walked by foot to Galilee, in northern Palestine, my family included. Shlomo Chafshosh, my great-grandfather, died from typhus due to the terrible conditions of the march. Esther, my grandmother, grew up in an orphanage in Tiberias.