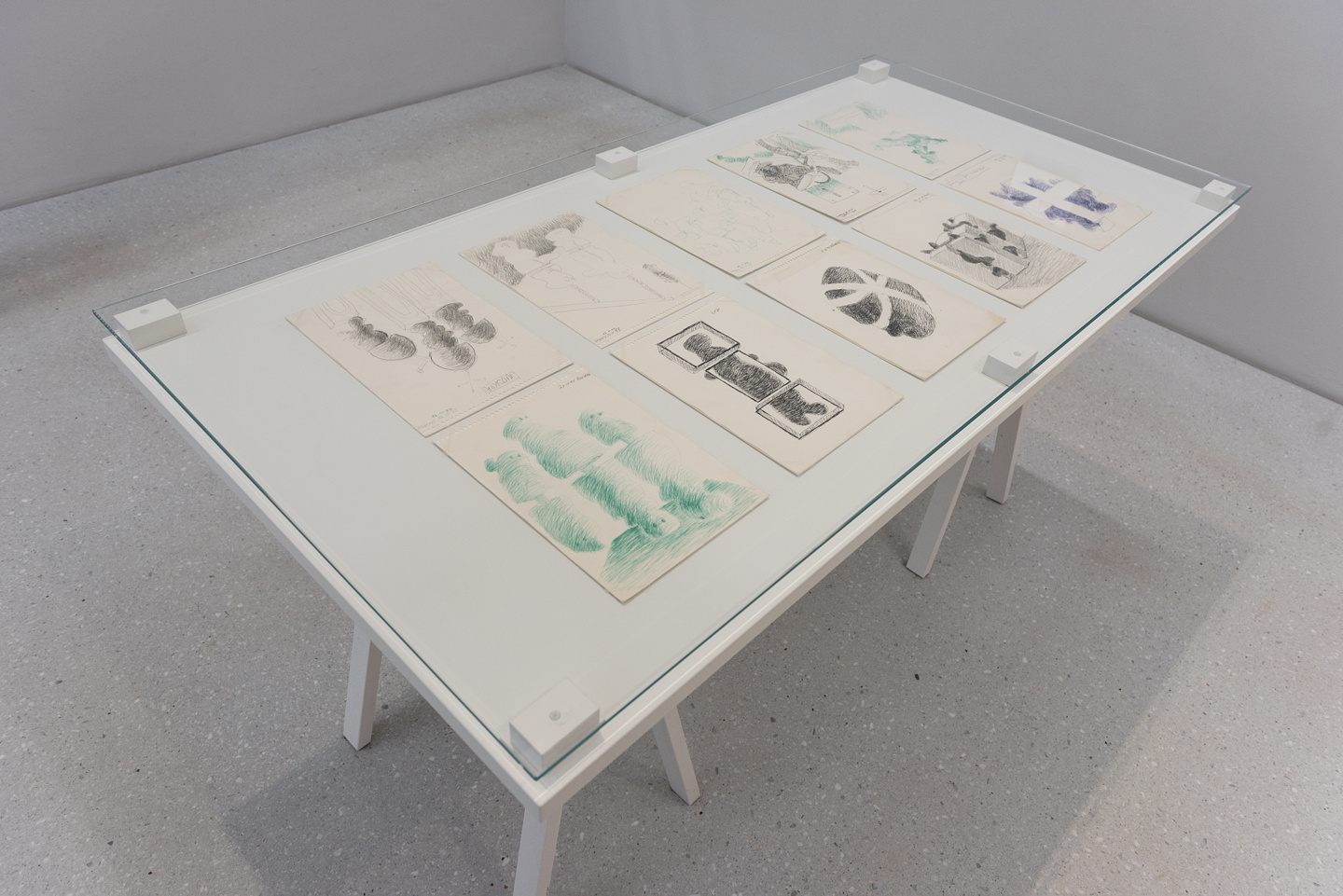

Agim Çavdarbasha, Sketchbook, 1998, installation view, Neue Galerie, Kassel, documenta 14, 2017, Foundation Çavdarbasha , photo: Milan Soremski

Agim Çavdarbasha’s sculptural work is part of the foundations of modern art in Kosovo. He studied at Yugolslav art academies (in Belgrade 1964–69 and Ljubljana 1970–71) within liberal circumstances that allowed for the development of individual creativity. Yugoslav sculpture included all kinds of qualities and movements, while Çavdarbasha himself tended to refer to a few great modern sculptors of world renown such as Hans Arp, Constantin Brâncuși, and Henry Moore.

In Çavdarbasha’s oeuvre we encounter series of works with abstract relations, such as those with spheres and cubes, or of groups of shapes, although the artist was in fact more interested in organic forms: the human figure, portraits, and animals. Sculpture for him was not just a cold and rational relationship between formal elements; rather he saw it as a reflection of narrative relationships complete with psychological tensions, emotions, and elements of drama. In the works he made out of materials such as plaster, wood, and marble, Çavdarbasha was not attentive to the realistic appearance of faces and figures. Instead he attempted to delve into the essence of the psychological movements or expressions that characterized certain social sensibilities.

In some of his work, as in that of his contemporaries, the influence of and reflection on social and political developments of the time is apparent. During the 1980s, Çavdarbasha created a series of artworks in which he combined organic forms with geometric ones—for example birds shut inside and enclosed by a cage’s bars—which obviously referred to the mass oppression of the rights of Albanians in Kosovo. That geopolitical situation ultimately led to the abrogation of Kosovo’s autonomy, and later to the war of 1998–99 and NATO’s military intervention.

However, Çavdarbasha’s most accomplished and original works are those that include an ensemble of figures, such as in Çifti (The Couple, 1974–75), Biseda (The Conversation, 1976) and Loja (The Game, 1982), as well his life’s masterpiece, Sofra (Round Low Table, 1973), in which he explored the possibility of depicting, through the mastery of reduction, the essence of the circumstances of a conversation, of the interplay and affinity in the relations between people. In contrast to Brâncuși, who mastered this subject mainly with geometric tools which veered into a mysticism of forms that were simplified to their utmost possible extremes, Çavdabasha’s sculpture went in another direction in reducing organic forms, where rational reinterpretation was not imposed on the material, but instead the artist himself followed the “essences” of the relations of real and living volumes. In this regard, he remained a realist. In other words, where Brâncuși and Arp pursued otherworldly ideal forms, Çavdabasha went after eidetic, worldly, living forms. His figures are always thick, fleshy, with a sort of condensed size and weight, bound to the earth and this world, yet reminiscent of the ancient shapes of pagan fertility idols.

In this vein, one of Çavdarbasha’s masterpieces is surely the ensemble of figures titled Gratë e Lubeniqit (The Women of Lybeniq, 1996), exhibited for the first time in 1997 at the Gallery Dodona in Pristina. The artist said that he was inspired by a group of women craning their necks to see from afar the male burial rites at the funeral of the Kosovar thinker Gani Bobi, in his birthplace in the village Lybeniq. Made of wood and with a wholly rustic appearance, in this piece the reduction of the figures down to two masses—the body and the oversized heads—is emphasized to depict, through an entirely coarse intervention, the rough drill marks of the women’s eyes, as well as the most elementary and distorted poses. The composition Gratë e Prishinës (Women of Prishtina, 1997) is similar, with the same dark eye sockets facing fear and terror, and which in this case Çavdarbasha depicts in a hovering state, as the figures have neither a pedestal nor base, but remain indefinitely suspended in the air from chains.

—Shkëlzen Maliqi